[dropcap letter=”T”]

he great architect Antoni Gaudí was a simple man, a man of the earth. His grandparents made boilers, stills, bells. They came from an old tradition of metal foundrymen, and he inherited their wisdom in the treatment of volume. Because Gaudí’s most important characteristic is that he played with architectural volumes in what was his paradise in childhood: nature in its primaeval state.

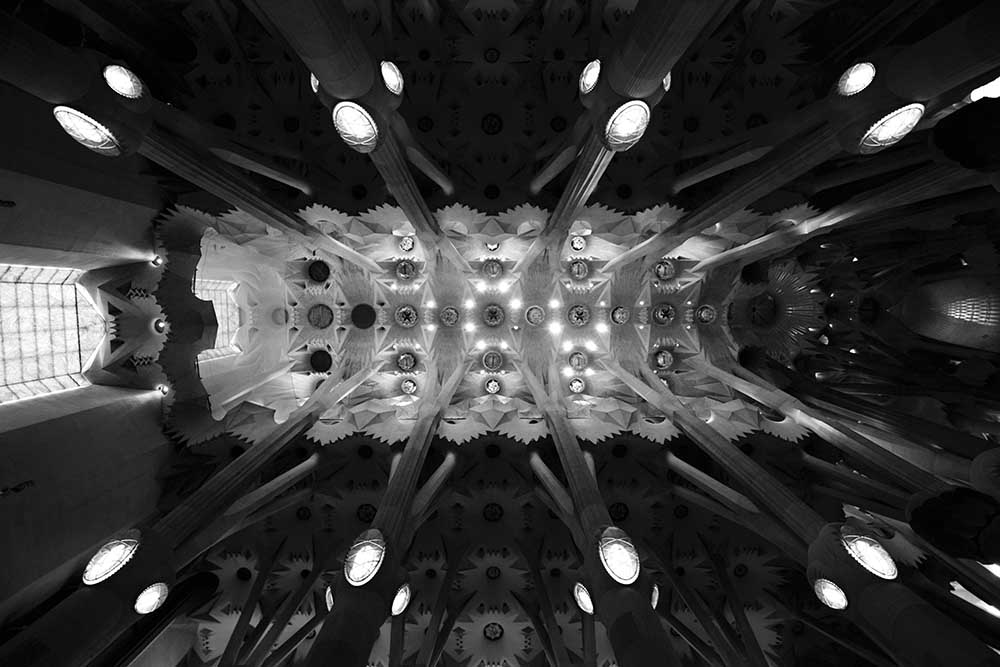

All his work is a wonder. Very expressive, very photogenic. That’s why the camera loves it so much. The Parc Güell, Casa Batlló, La Pedrera, the Sagrada Familia, have all incited millions and millions of pictures. If you take a good look at it, Gaudí’s work is full of well-resolved details, of creative discoveries. “Original—he would say—is to return to the origin.”

Gaudí commanded not only volumes and shapes, but also the harmonic relationship between those volumes and shapes. And numbers, geometry: the old Pythagorean tradition. He defined himself as a geometrician. There are analogical links between between geometry, generation and genius. The Greek prefix geo- refers to Gæa or Mother Earth—and her homologue Demeter, the goddess of generation par excellence.

Gaudí’s work shows no straight lines since he considered that they do not occur in nature. This may not be quite precise, however. The enigmatic crystallization of minerals underground cannot be disregarded. “I am a geometrician, which means concise,” he declared of himself. Or “architecture is the first archi, in other words, the first guiding principle.”

He has been the object of study recently, from the point of view of scientific positivism. But much more than a technician, architect Gaudí was an artist. He mastered materials as a scientist, he transformed them as a creative. Beyond the exact measurement of his multifarious accomplishments, we should be interested in his mysterious creative genius, that impulse of the spirit that made him so special.

Gaudí cannot be understood without traditional popular religiousness. Or without the artisan spirit of his ancestors and collaborators—the moral of a job well done, of common sense, a practical sense, a sense of reality as it is. Without this his manner of work, so meticulous, cannot be understood, and his absolute willingness as a collaborator of the Most High in the recreation—the human recreation—of His work.

Gaudí revered nature and observed the evolutionary process in all its mineral, vegetable or animal forms. There is in Gaudí the deepest sense of a direct connection between the hands of the artisan and cosmic consciousness. Everything in Gaudí is presented in communion with this transcendent reality. Beyond accessory aspects, this was what most determined his creative process.

And that light, that constant Mediterranean light which, at a 45 degree angle, “gives harmony to form—as he himself would say—since it is neither horizontal nor vertical.” The light that comes down to us like the edge of a set square is the light that brings nuances, which lights up the detail. While zenithal light, which falls dead vertical, like a stone, so characteristic of the tropics, makes a world of light and shadow, black and white, dual. And boreal light, which comes across the horizon, submerges visible reality in a nebula, in a ghostly confusion.

One might speak of Gaudí’s paradigm: a way of understanding architecture—and design, and art in general—consisting of searching for, and finding, harmony with nature. And not detaching from it or imposing a touch of artificiality. Because in order to express something in a different, innovative way, first you must have perceived something that is not a mere projection of what is already known to us.

To innovate, to renew, to invent—and Gaudí did this constantly—it is necessary to position oneself at ground zero of one’s experience and to know how to eliminate the interference of what is routine, and not repeat the cosy staple, but to search for new ways. Is this not what an artist does, particularly the contemporary artist? 20th century art cannot be explained without this persistent process of unlearning.

In Barcelona there are splendid examples of the genius of this wonderful architect. All the work by this genius, this great architect, and also this great sculptor, is like an enigmatic forest of images, a maze where we may find keys to the knowledge of the most authentic human nature. Because, rather than an aesthetic experience, admiring Gaudí’s work can also be, as he himself would have wanted, a spiritual experience.