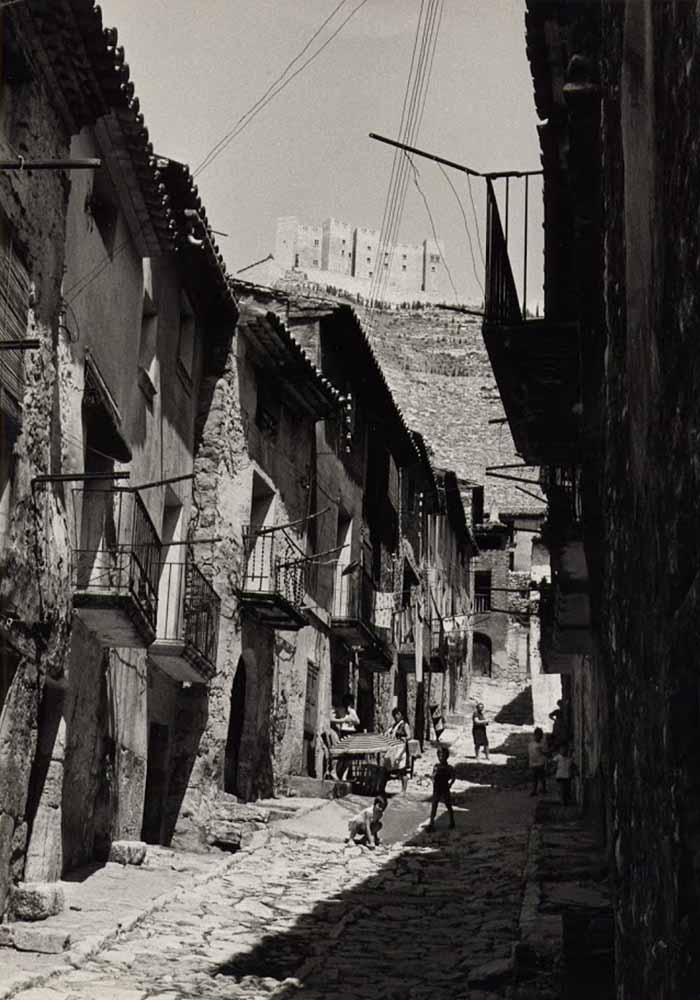

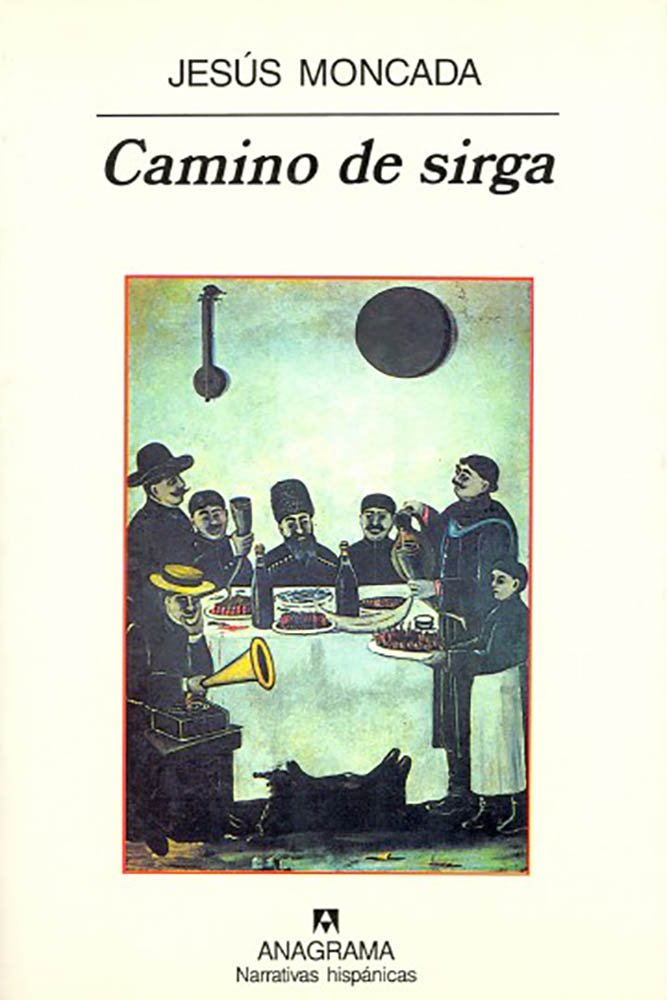

Mequinensa, Lo Poble—the village, in the vernacular—began to exist through Jesus Moncada’s typewriter keys, and no earlier. This was twenty years after the demolitions and the waters of the huge new reservoir sank beams and walls and swept away the paths, walks, orchards, the lost row boats, the wicker baskets full of onions and folding back wooden chairs on which men fell asleep at coffee time. Camí de sirga—The Towpath, the best-known work by the Maquinensa writer, or as he liked to call himself, a Catalan writer from La Franja—the strip of Catalan-speaking land within the neighbouring region of Aragon— this year sees the 30th anniversary of its first edition in Catalan. It has been translated into fifteen languages and has enjoyed a notable and well-deserved reception everywhere. The novel harks back to a story based on the effect that key chapters in the history of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries had on the men and women of the old Mequinensa, which was rebuilt—without soul—in the dale where one of the three rivers flows feeding the Aiguabarreig—the confluence; the Segre.

Recognition for Moncada came late and poor, as is so often the case in cultural spheres without the support of a State. Late because Moncada scraped by for a good part of his years, and this prevented him from fully developing the production he would have been capable of. And poor, because Moncada’s merit does not arise from The Towpath, or at least it does not start or end with the novel. Jesús Moncada’s merit has been to establish a literary capital for an orphan territory. Until then, no other place had been able to adopt the condition, orphaned as it was of old Mequinensa, not even by Lleida, the natural geographical capital, which accrues an age-old deficit of consideration, courtesy and care for the region. This doubtlessly provides clues as to the lack of generosity, not to mention the parsimony and often haplessness, of that part of the Terra de Ponent—the land of western Catalonia. And perhaps likewise explained by the harsh conditions that its people have had to endure over time.

It is appropriate to look back upon and project Moncada’s literature as an example of a beacon to combat the muddled confusion of a territory that, like many others, have been crushed under the dirty boot of penury, and has had to escape through the only available crack in the wall: one that has led the region to a tenuous way of life, where all that matters is killing time and filling pockets

For those of us who have learned to love the Terra de Ponent—beyond its primary and widely applied moniker—which means resigning oneself to the poor rewards that the effort put into the land returns, Moncada is the father-figure who has given us back a motherland in this western meridian land; a rich lode, sometimes comparable to the great civilizations forgotten by the chronicles of humanity, which offers refuge for the lonely and the souls who seek the warmth of a tavern and a glass of cheap rum. Works such as the erstwhile Històries de la mà esquerra—Left Hand Stories or El cafè de la granota—The Frog Cafè, are collections of stories where, having erased the physical boundaries imposed on the demarcation of La Franja, Moncada details the scope of his world. And the later works merely consolidate this, a relief for the souls of those of us who feel part of or have been born into it. With it, our identity remains, unchanging, without pretensions, away from impostures, rooted in the domestic truth of the blessing in a wisp of sou’wester during summer dog days, the perfume of the rosemary and the thyme in the hills that circle the plain, of the winter fog that obliterates us from the map, the buses croaking along the black strip of road, the labourers with cigarettes hanging from the corner of their mouths while they strip the trees in the terraced fields, the lights on the Fraga bridge reflected in the river Cinca, the Faió Vell bell tower, of the remote perfume of a fig tree that lives but from raindrops.

That is why it is appropriate to look back upon and project Moncada’s literature as an example of a beacon to combat the muddled confusion of a territory that, like many others, have been crushed under the dirty boot of penury, and has had to escape through the only available crack in the wall: one that has led the region to a tenuous way of life, where all that matters is killing time and filling pockets, even if this means harming the environment and its very sprit. In one of the fragments of The Towpath, Moncada gives voice to one Joanet del Pla: “They mean to make electricity on our ribs—he says—they will build two reservoirs, with us in the middle. Dammit!”—he concludes. And I think maybe not. Maybe one day we will consider it a stroke of luck; The day that the capital that now lies in the old village under the Ebro river is replaced, because societies transmute and capitals change. The day that happens, if it happens, Mequinensa will be on the threshold of mythology, or almost, and Ponent will then be open to abundance.