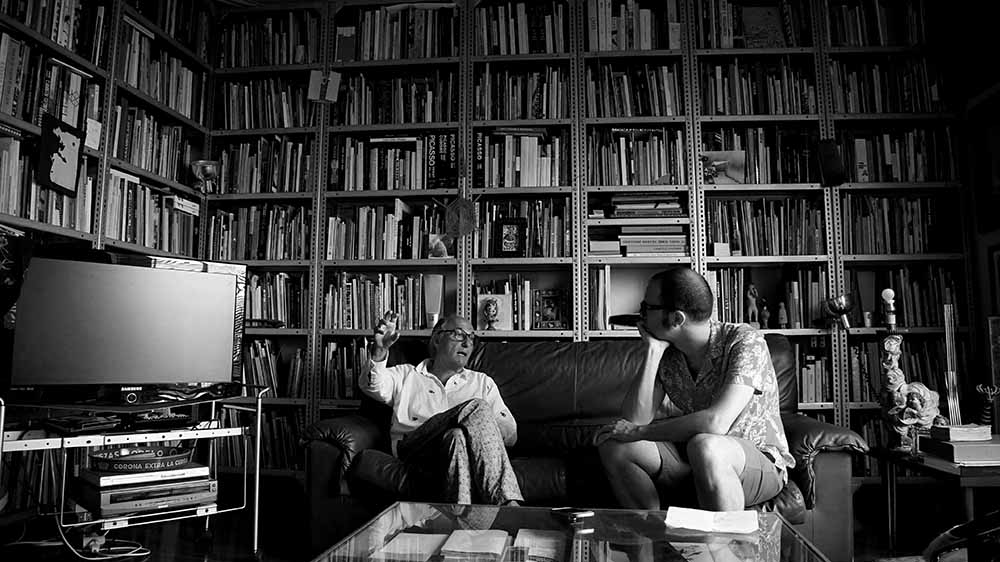

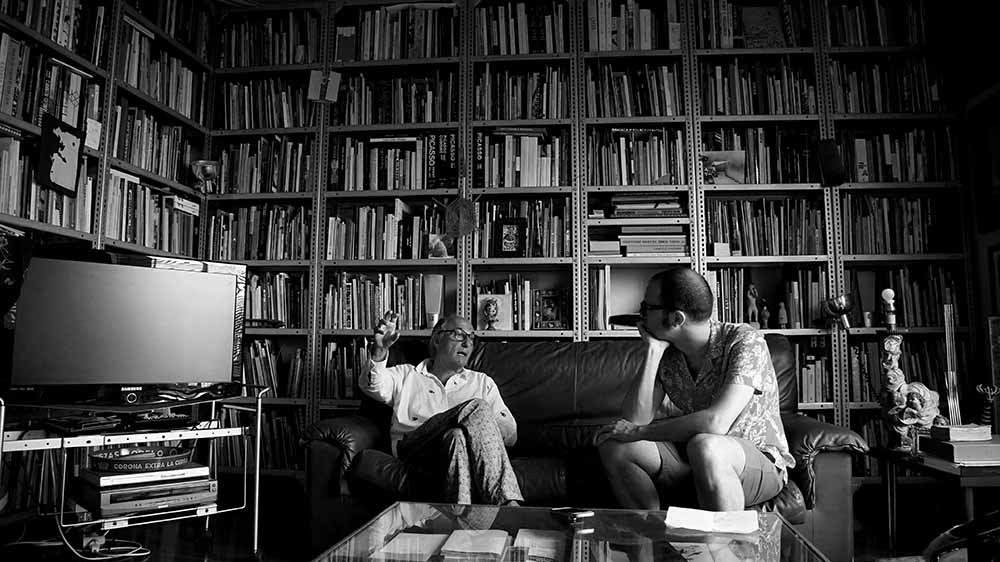

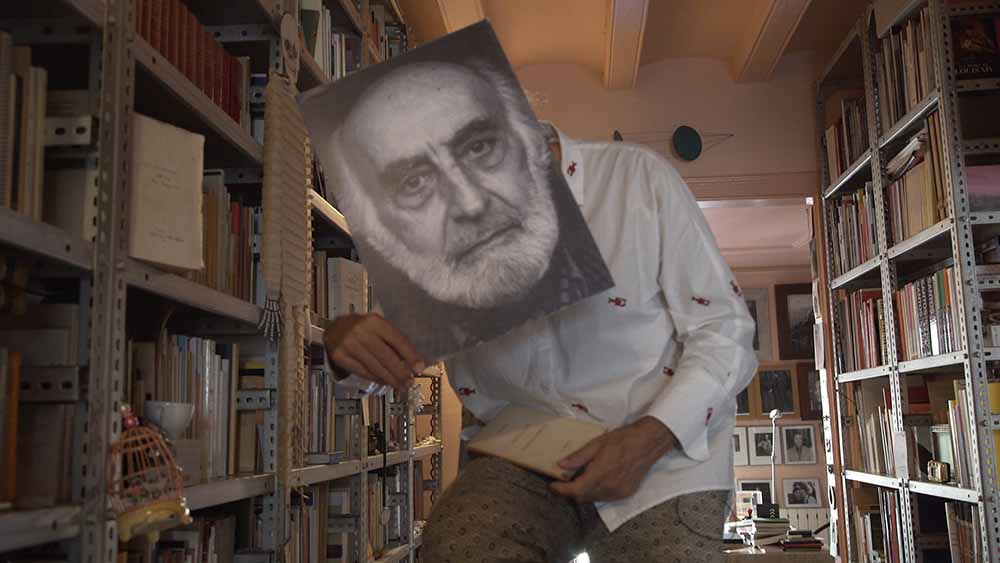

Poet Vicenç Altaió talks to Albert Forns and Morrosko Vila-San-Juan for The New Barcelona Post about his relationship with JV Foix, Joan Brossa, Josep Palau i Fabre, Perejaume, Antoni Tàpies and Albert Serra:

You have a spectacular book collection. Have you read everything?

Everything..

How did they become part of your life? Books, I mean. Did your parents have a big collection at home?

No, at home there weren’t all that many books, but there was a great love for them. My parents didn’t read much—we were six siblings—but there were always books present, we would get them for our birthdays and such. Two moments I recall very well: on the day I was 16, I was given a book by Amado Nervo, a poet who, besides poet, translator, novelist and academic Pere Gimferrer, I should think no one else in Catalonia knows right now. But that was what I read, and a poet was what I wanted to be. I also fondly remember Strength to Love by Martin Luther King—published here as La força d’estimar by Edicions La Mirada—and Pierre Teilhard de Chardin’s books.

And then there was the book and gift shop, run by a monk who had given up the cloth, in Mollet, the next town. I remember my father, who was a friend of his, sent me there: “Go and see him; he does what you like.” And I would go there on foot, 7 kilometres—4½ miles, and I would help him. And this guy gave me a lot to read, the likes of Espriu, but what impressed me most was that upon returning from a trip he made to Mesopotamia, he showed me a copy of Salvador Espriu’s poetic works he had submerged in the Euphrates River. And for me that was an artistic discovery, because I saw that a book can also be an object bearing meaning, in this case an Espriu bathed in the foundational waters of civilization.

“Come, come, there are none of mine left” said JV Foix; (…) I read Foix without understanding anything, because I didn’t yet have a sense of meaning of the language or the word

And what contact did you have with Catalan literature?

I was little and at school they would stick it all to us in Spanish: they would tell us about Federico García Lorca, already at that time, and also Ruben Darío and Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer, but they would never mention any Catalan writers. On the other hand, at home I would see my grandfather’s or my parents’ books, published in Catalan, because by then there was Edicions 62—a publisher which focused on books in Catalan. There was this modern trend, the gauche divine—a fashionable left of movers and shakers—and so I lived both cultures in a conventional way. One was the official one, the other was the natural one. The Franco regime had been very effective, because there was a part of the Catalan culture that I totally ignored, and it was not until I got to university that I started to ask questions.

It is at university when you encounter Foix, Brossa and the great poets.

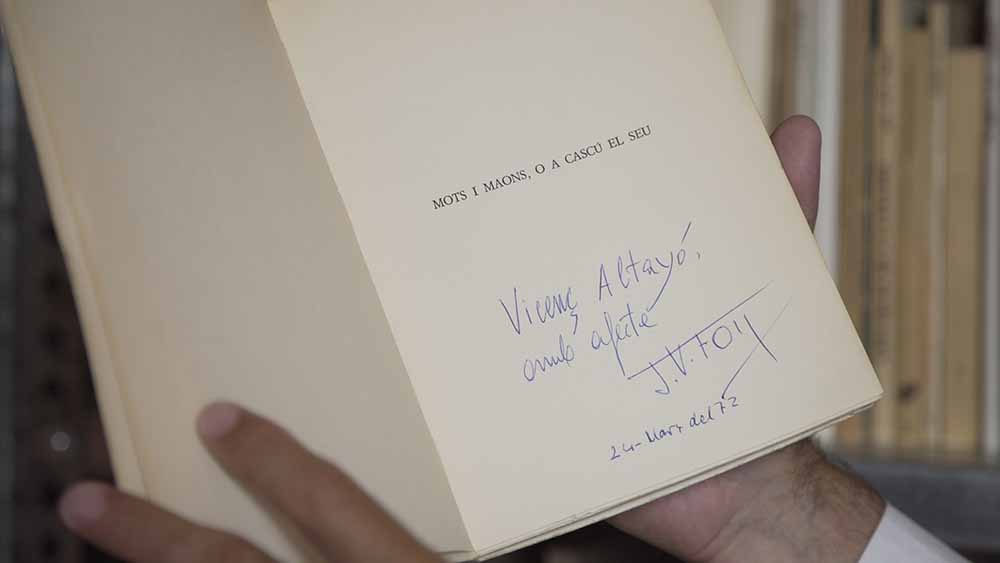

At the Barcelona Autonomous University I discover and become aware of that unknown world of Catalan literature, and Joaquim Molas guided us with readings, and had us read Josep Carner’s Nabí and the Elegies de Bierville by Carles Riba. And at one time he had us choose a poet for a project, of which there was Sagarra, Espriu, Carner, Pere Quart and JV Foix. And the name of Foix was the one I found to be least familiar, and it was through that obscurity that I came upon a poet who has been of great clarity for me, determining me. I came to his house, I knocked at the door—I was 17 years old and he was about to reach 80—and when he opened, I apologized, and the first thing Foix said was “Come, come”—he would address everyone with the deferential vos—“come, there are none of mine left.” In other words, it was an encounter between someone who had seen all of their life’s cultural framework depart, with a very young person who did not know anything about that cultural life. “Come, come, it is now up to you,” he said: Foix was very clearly aware that he was passing on the baton to us.

Did you like his poetry?

I read Foix without understanding anything, because I didn’t yet have a sense of meaning of the language or the word, and I understood that it is thanks to difficulty that you learn a language, diving into dictionaries, unlike that which the field of common language communication contends.

How did JV Foix mark you?

From Foix I learned extraordinary things, of which surely the most powerful was that we were young rebels, with long hair, but he repeatedly gave me the same advice: “Altaió, Altaió: don’t think that because you wear your hair long and greasy and your nails dirty that you will be more of an artist than others.” Wham! In one single sentence he educated you in hygienic rationalism, in aesthetics, in the sense of work. And this from an oneirist out of surrealism… And then he would take me to his library and pull out a classic from the Bernat Metge collection, open it and make me read the same thing he had just said, for example “don’t think that because you wear…” And then he would say, “See? Plotinus.” And he taught you that, when it comes down to it, human substance is always the same and it is the form that changes. We learned a lot from Foix.

“The world cannot go well if the Filmoteca—the Catalan film archive—closes in summer,” versed the last dedication Brossa wrote me; (…) Brossa was close to the young artists and he would give them free rein, and there I learned to do the same

At the PEN Catalan Centre, you come into contact with Palau i Fabre. A dark character, you often say.

Palau i Fabre’s conflict was that of the adolescent, which is what we were then, so he was the poet closest to me. And he knew how to proffer that sense of rebelliousness and backlash of youth. The first prologue I write, co-authored with Jaume Creus, is for a book by Palau i Fabre. He was disdained at college, primarily due to his generation, because Palau i Fabre flees and goes into exile at a very young age, and it is when abroad where he meets open-minded people like Octavio Paz, Pablo Picasso… When Jaume Creus and I went to see him for the first time after he returned from Llançà—a fishing village in the NE of Catalonia—and from exile in Paris, we found him living in gloom, lit only by a low-voltage bulb. But when we asked after his relationship with Antonin Artaud, we saw his eyes open wildly as he realized there was someone who wanted to listen to him. It was odd because, when he went out, it was always in very flowery shirts, a stylistic feature I may have inherited from him. But despite this bright side, he lived in a very closed inner world. With Palau i Fabre we experienced extraordinary moments. Years later, I remember seeing him one day at the Joan Prats gallery, in his wheelchair before of a painting by Perejaume, in which there was a horizon that was like a baguette, and he sat there staring at it. People would go by, and he would not pay them the slightest heed. I went for a beer with a friend to catch up on our news, and after a long conversation, when we got back he was still there sitting, looking at the same picture.

Did this dark side to Palau i Fabre come from a lack of social recognition?

He was not recognized. He had written great works as a poet, but he closed that period very soon. He then started his theatrical cycle, but there was no theatre in Catalan then. He had a story or two to tell, but he had not started yet. And it was through contact with the younger generation that we managed to get him back on scene. Then, naturally, the market came and publisher Proa took in his work and put him where he belonged, so that today nobody objects to the literary value of the work of his generation. But they are authors that simply did not exist for almost anyone 40 years ago.

Before cremating Brossa’s coffin, we opened it and we tossed in a deck of cards

You often visited Joan Brossa too, ever since you’d been a student, right? In that chaotic study, full of papers on the floor: “Don’t mess anything up!” says photographer Pilar Aymerich he told her the day she went to shoot his portrait.

I visited him a lot because one day I would be asking him for an object poem for Èczema magazine, on another there would be an Italian magazine that wanted to do something with him… All those papers were a bit staged, because one day I went, there were none because he had had a flood and they were spoilt. But the next time I went, there were papers everywhere again. Brossa would leave notes, and I have a few I’ve put away [he goes to look for them]. Look, this must be from 1975: “Altaió my friend, I have to leave, I’ve waited until now, here is the poem as we agreed, I’ll be expecting you on Friday at about 6pm.”

They’re notes he would leave me and I kept. This one was given me by Brossa’s partner Pepa Llopis when he died. “The tickets have been sorted out. Vicenç Altaió will use them. He’ll also take care of the petrol.” It was a trip to Valencia. They are details of everyday life. I didn’t have many books dedicated by Brossa, and shortly before he died, in a strange fit of intuition, I went to see him there in Carrer Balmes, and I clearly remember him complaining to me: “The world cannot go well if the Filmoteca—the Catalan film archive—closes in summer.”

Perejaume lives the magical and the real worlds all at once

It’s prodigious, your keeping all these papers and notes.

Foix gave me one piece of advice: “When you grow up, what do you want to be?” “Like you, a poet,” I told him. “Well, keep your day job.” And so I did. I was very clear that my other job would not be as a pastry cook or going back into the family business I had chosen to leave: my second job would be in culture. And I saw that there was a potential in all of that. I was born shambolic, but when I met Foix at age 17, I turned methodical. It was that “don’t think that because you wear your hair long and greasy and your nails dirty that you will be more of an artist than others.” Here in this flat I have the paperwork for all the books I prepared, in that display cabinet, all the books I have published, and in all these bookshelves are the books I have taken part in, whether with prologues, epilogues or texts in collective books. And here are all the books of the KRTU—the Centre for New Trends with Multidisciplinary Vocation, on this shelf are all those published at the Santa Mònica Art Centre, and then there are all the object magazines…

Brossa died that December, months after the dedication, and I took charge of his funeral. I have had to organize many funerals of our culture, of good departed friends. I remember that I was here at home and Jaume Josa, who often chauffeured Brossa, called and said “Man, I have to give you some bad news, Brossa has fallen down the stairs and is dead. Pepa and the family have asked us to take care of the funeral.” “The first thing we have to do,” I told Jaume, “is to say that, according to the wishes of the family and of Brossa himself, there will be no protocol and everything will be the VIP row.” That way we saved ourselves any pressure from museum directors, politicians, ministers of culture and so on. Everyone came to say farewell to the departed with the same rank, which is a very republican way, which is precisely what Brossa was. And the funeral included music by composer Mestres Quadreny and Valencian musician Carles Santos, and before cremating the coffin—and very few people know this—we opened it and we tossed in a deck of cards. We told the family so nobody would consider it desecration, but we thought that Brossa had to leave the world with some unmarked cards.

Before the KRTU and Santa Mònica, you were the commissioner of Espai 10 at the Joan Miró Foundation. Did you ever meet Miró?

I never got to know him properly, because Miró did not speak much. Miró looked at you, he had bright, child-like eyes, he would smile, the times I met him it was always like that. We did not have conversations. Not with Brossa either, with whom I was very friendly, but we did not chat much. When we came out of an inauguration, he made sure the conversation would end so as to begin the theatre of life, and he would create action poems live, what we have later seen turned into object poems on the art circuit: he would take a cork and stick in a fish bone, and so on. There are people like Brossa who transform their lives into a work of art, but with whom you do not have an intellectual relationship. But he was close to the young artists and he would give them free rein, and there I learned to do the same, so throughout life I have given many full confidence and the free run of things. Brossa helped us a lot with the Èczema magazine, and he got us the Ciutat de Barcelona award, despite being so young.

You met Perejaume through him.

One of the first things that Joan Brossa tells me when we started meeting was “I’ve met someone just like you, go and see him,” and he meant Perejaume. And so I went to see the very young Perejaume, who I am not sure if at that time still lived in Sant Pol de Mar, where his parents were from.

Perejaume lives the magical and the real worlds all at once. As a generation, with Perejaume we have in common this participation in places without boundaries. I have always believed that Perejaume was the first postmodernist after the straight line of modernity, those who had a style of writing that was always the same, and where each one was because they had a different, identifiable style, whether Miró, Tàpies or Chillida. But not he: he is recognizable, but not in the style of his handwriting.

With Perejaume we did a very nice issue of Èczema magazine, where there was a balloon with one of his first poems, in the Brossian manner. The poem was printed on a hot air balloon, and the balloon had the peculiarity that when air was blown into it, it took the shape of the world. You lit the wick, a cotton-wool swab with alcohol, and as it burned you found that, as the balloon swelled up, you could read the sonnet, and when halfway through the poem it would fly out of your hands and upwards into the sky, where depending on the temperature and the wind, it would end up with an anonymous reader. It was a very early, but very authentic metaphor.

Tàpies had an enormous influence, because any opinion of his could be decisive for another artist

Let’s talk about Antoni Tàpies. After Miró and Dalí, he is the most prominent Catalan painter, and despite that, I have always sensed a certain rancour towards his figure in the art world here

Look, I’ve heard these trite clichés too, but I spend very little time on gossip, I don’t believe in this Hello! celebrity magazine kind of chit chat transferred to the world of culture. I have maintained cultural and professional relationships, and friendship with all these people. And one will be like this, another will be like that, but I have always found a nice way to be with them. There are artists who will only work for themselves, but the moment we have had any form of exchange, it has always been positive.

When we prepared the exhibition on Palau i Fabre with Julià Guillamon, for example, we had a crisis one day that Julià discovered some letters that Palau i Fabre did not like, and the man stopped the entire operation when the exhibition was about to open. So I went to see him, and that reserved introvert opened up to me and apologized and excused himself. And I did not convince him by scolding him, but by saying “listen, this money is not ours. It’s the country’s, it’s Catalonia that has put the money up for your exhibition!” And wham, the instant he hears that, he automatically asks forgiveness.

I went to see Tàpies many times and there was complicity and friendship, he even made me a drawing or two for some front pages. Perhaps he did not come to understand the sober treatment I gave some of the things that he had passed me, but I have memories of a great intellectual power, and towards the end of his life, memories of extreme tenderness. One of the last times, I brought along a good friend, Alfredo Jaar who was interested in the relationship between art and politics, and I remember Tàpies chatting with him all the time with his hand laid on mine, and I couldn’t believe it, it was a time of great tenderness because that just wasn’t him.

So it happens that sometimes people who have power are very influential, and their opinion can cause real upsets. I can be talking with young poets, for example, and naturally giving my opinion on the last book I have just read, and that to your ears might be magnified. And Tàpies had an enormous influence in the art world because any opinion of his could be decisive for another artist.

Albert Serra has given radical life a cinematographic function

Did you ever go to Campins?

Definitely, I had the privilege of going several times to Campins—in the Montseny mountains where Tàpies had a farmhouse—to see the work he had done during the summer. In the first year all that huge amount of work struck me, none of my friends did that amount of work. But the following year I understood that there was a systematization of formats, of technique, a kind of replication. And in winter you would see him at home, talking about the world, reading books on science, religion, and publishing books, usually poetry.

And finally there is Albert Serra. Do you know him from Cadaqués?

No, we met earlier. A girl, an artist who’s doing a great job on Marcel Proust, spoke to me about this Catalan guy “like you” who was beginning to enjoy some success in Paris leaving everyone stupefied, and with whom we shared imaginary, and she reminded me of Brossa: “I know someone just like you, go and see him.” And I called him and he said “I know a lot about you, I’ve read your books,” and we arranged to meet at the Empordà Museum in Figueres—in NE Catalonia—for me to sign the books before going to an event at the Museu del Joguet—the Toy Museum—on film-maker Pere Portabella. And I find Albert Serra holding two bags full of books. First, I thought that he had filled the bags with everything I had written, but to my surprise, one was filled with the same book, Biathànatos o L’elogi del suïcidi—Biathanatos or In Praise of Suicide—and the other was filled with Tràfic d’idees—Trafficking Ideas. He had 20 copies of each, because at that time he had the habit of making gifts of books to others, and he gave them to friends. It was a great moment, I took them and, as if nothing, signed them one by one. And in Cadaqués we saw each other one day, perhaps 10 years ago now. I was writing at the back of the house, Albert Serra came by and invited me to a party, because he and his community had rented an apartment in the village. And that evening we chatted from half past 7 until 4 in the morning, when they called me to tell me that Lanfranco Bombelli had died. We spent the night talking face to face, without moving from the very same tile, so to say. And since there were a lot of people there from Cadaqués, the next day the town was full of the meeting between two fools who had spent eight hours chatting.

What is it that unites you with Serra?

We have true intellectual passion. Serra has given radical life a cinematographic function, and obviously many people will not be able to understand his way of working, or will even suffer from it. But I, who have lived with other similar radicalisms, with Pasolini or Palau i Fabre, am prepared to let him work and meet at places that are totally improper and original.

Serra told me not to read anything about Casanova, and obviously I read everything

And with this “let him work,” you let him turn you into Casanova.

Yes, in the film Història de la meva mort—Story of My Death. Serra calls me one day saying let’s have lunch, and he tells me that he thought that I could play the role of Casanova. “But what do I have to do?” I asked. And he says, “What you have to take into account is, above all, that in Romania, where we are going to shoot, there are many wild bears, and since it is possible that in the middle of the shooting we may run into one, you have to remember: take off your clothes and run down the mountain, not in a straight line, but zigzagging.” “Ah, I see,” I said, “like Miró, who drew those lines in every direction.” Well, it was that easy for us to understand each other.

He told me not to read anything about Casanova, and obviously I read everything because everything is the way I am, shredded, with culture being life, undistinguishable, and that it should be a hybrid of what is original in what we will contribute. And we finally let Serra do his philological work, because we record reality in the present continuous, and then the edit is the nitty-gritty: knowing how to discern and build moments. His method at that time was to record everything in life, and then do a tireless job of seeing everything and assembling it according to criteria that may not be logical or syntactic, but may be a combination of colours, pauses, and so on. The film is very peculiar, very original and very hard, but when we went to Locarno, the great European festival of art house cinema, was soon super-beloved, and people were able to see it and highlight it. Now Serra has become the greatest Catalan artist with the greatest international recognition, after Dalí, Miró and, of course, Tàpies.