[dropcap letter=”I”]

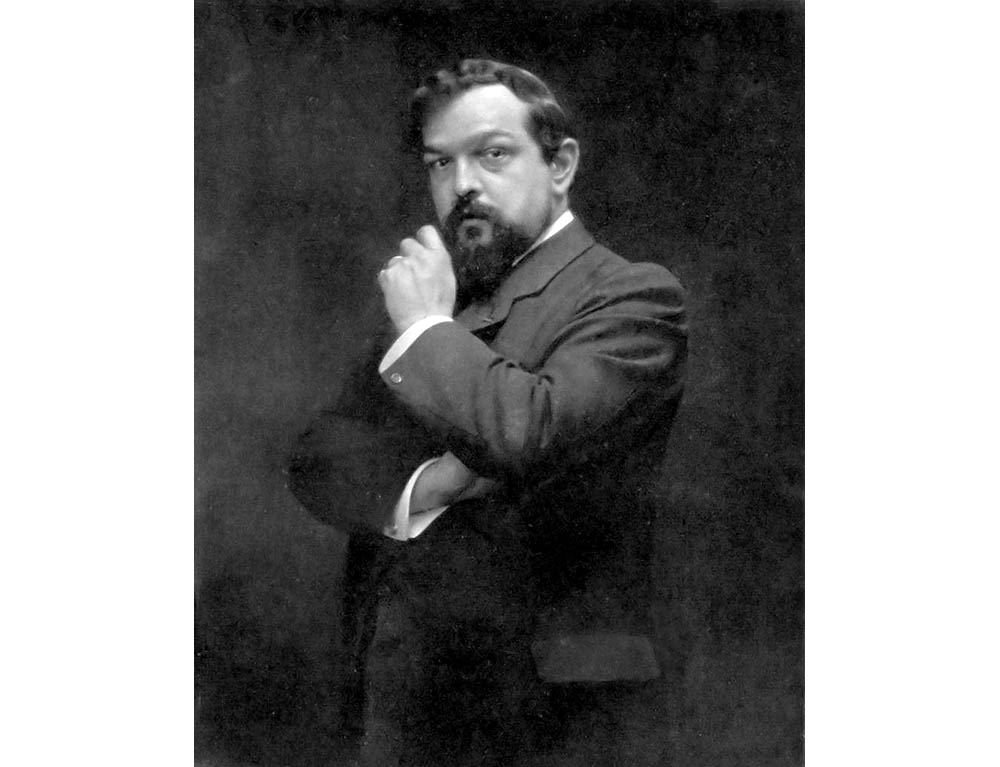

f one had to say which composer has been plugged into the brain of those born in the seventies, that would certainly be Claude Debussy. Planeta imaginari, one of the first youth programs broadcast by TVE Saturday morning in Catalan, used its Arabesque no. 1; an undulating melody that suggested a dream-like state of mind, and that today is activated on my cell phone every time they call me. Debussy is also behind one of the most revolutionary ballets of the early twentieth century: Prélude à l’après-midi of a faune. In this piece, an infatuated Nijinsky scandalized the audience of the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées in Paris outlining a gesture of onanism. There is also the Debussy who composed Pelléas et Mélinsande, an opera of Wagnerian inspiration that fascinated his contemporary Marcel Proust. One of the characters of In Search for Lost Time, Madame Verdurin, grows eye-bags due to Debussy, which causes her an addiction “stronger than cocaine.”

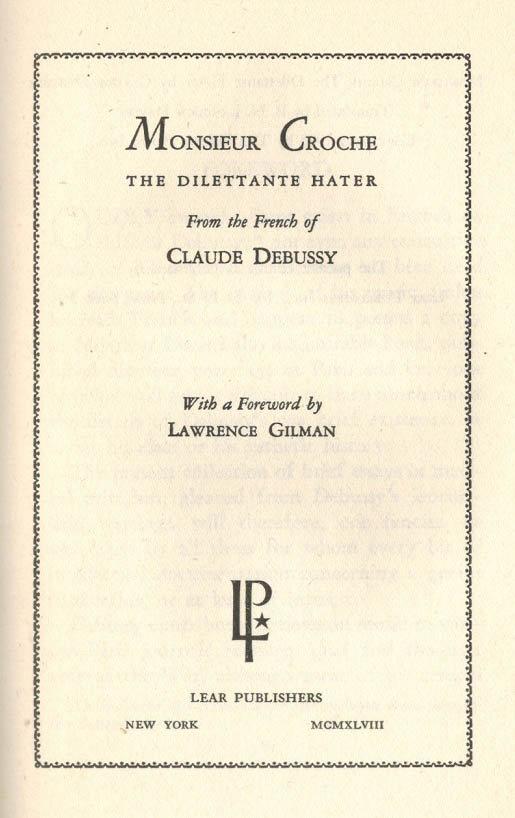

From the aspects of the composer considered one hundred years after his death -mysterious, when one listens to his ancient Ephigraphes or a musician outside the norm, it is the case of La Chute de la Maison Usher– perhaps his least known aspect is that of a musical critic and theoretician. It was in the small Breton municipality of Bécherel, paradise of literature, where some years ago fell into my hands Claude Debussy’s Monsieur Croche Antidilettante (Gallimard, 1926). The first edition is from 1921. The volume includes the reviews that the composer made between 1901 and 1914 intermittently in several publications. He began with La Revue Blanche and then wrote for Gil Blas and S.I.M. But Debussy -friend of Mallarmé, Rimbaud and Verlaine- did not merely write conventional reviews. He created out of nowhere a character, Mr. Croche (meaning “quaver”), with whom he talks in order to expose his aesthetics. Antidilettante is the “profession” of this incisive, asthmatic and nocturnal speaker: “Mr. Croche loves music and that is his main topic of conversation. For him, music is not a fantasy, but a serious affair”. Later, Debussy was evoked by a lost friend: “He spoke very low, he never laughed, sometimes he underlined his conversation with a dumb smile that began with his nose and wrinkled his face as a calm water where a stone is thrown”.

Mr Croche blames the audience for his “indifference” and the “specialists”, whom he considers close minded. The music? He tries to forget about it, because it bothers when trying to listen to the one he still does not know. “I try to see in the works the variety of movements that made them born, and what they have as inner life”. Croche defends “impressions”, a concept that leaves “the freedom to preserve his emotion from any parasitic aesthetics” and reproaches the other musicians for not stopping to hear “the music that is inscribed in nature”. “You do not have to listen to the advice of anybody, but to the wind that goes by and tells the story of the world”. Despite his wisdom, Croche disappears after three chronicles and Debussy is the one who takes the floor. His method is startling: Can a score be whistled, or not? This comes to be its scale to separate the good from the bad composers. The “great” Bach, for example, cannot be whistled; Wagner, yes. Saint-Saëns, Massenet… are not amongst his favorites, whereas R. Strauss seduces him because “there is sun in his music”, not forgetting Mussorgsky, his idol. “Today’s music is increasingly accompanied by sentimental or tragic anecdotes”, he regrets. Instead, believes that we should give up “parasitic developments that spoil beautiful things” and release music from certain “mania of form”. “It is not about uploading the echoes that are repeated with excessive repetition, but taking advantage of them to prolong the harmonic dream in the soul of the people. The mysterious collaboration of the curves of the air, the movement of the leaves and the perfume of flowers is fulfilled, since music is able to gather all the elements in such a natural understanding, which seems to be part of each one of them”.

Mr Croche blames the audience for his “indifference” and the “specialists”, whom he considers close minded. The music? He tries to forget about it, because it bothers when trying to listen to the one he still does not know. “I try to see in the works the variety of movements that made them born, and what they have as inner life”. Croche defends “impressions”, a concept that leaves “the freedom to preserve his emotion from any parasitic aesthetics” and reproaches the other musicians for not stopping to hear “the music that is inscribed in nature”. “You do not have to listen to the advice of anybody, but to the wind that goes by and tells the story of the world”. Despite his wisdom, Croche disappears after three chronicles and Debussy is the one who takes the floor. His method is startling: Can a score be whistled, or not? This comes to be its scale to separate the good from the bad composers. The “great” Bach, for example, cannot be whistled; Wagner, yes. Saint-Saëns, Massenet… are not amongst his favorites, whereas R. Strauss seduces him because “there is sun in his music”, not forgetting Mussorgsky, his idol. “Today’s music is increasingly accompanied by sentimental or tragic anecdotes”, he regrets. Instead, believes that we should give up “parasitic developments that spoil beautiful things” and release music from certain “mania of form”. “It is not about uploading the echoes that are repeated with excessive repetition, but taking advantage of them to prolong the harmonic dream in the soul of the people. The mysterious collaboration of the curves of the air, the movement of the leaves and the perfume of flowers is fulfilled, since music is able to gather all the elements in such a natural understanding, which seems to be part of each one of them”.

Achille-Claude Debussy died on March 25th, 1918, victim of cancer at the age of 55, forgotten by everyone and not having heard about the end of the Great War. His impressionist seed continues to live in 21st century composers, such as the Finnish Kaija Saariaho. Maybe that’s why one of his articles, “L’oubli”, demands our attention more than ever: “I have no intention of contributing to the history of music. Just wanted to insinuate that we might be wrong if we always play the same works, since it can make people believe that music was born yesterday, when in fact it has a past from which the ashes should be removed: these contain the unstoppable flame to which the present will always owe a part of its splendor”.

Featured images:

1. Portrait of Claude Debussy. June, 1908. Photo by LIFE Photo Archive

2. Page of the book The dilettante Hater, by Monsieur Croche.