How is urban planning adapting to the major economic and social changes in our century?

Our economic, technological and social system is being radically transformed. In the 20th-century industrial city, the economy is based on factories as production centres, and they are located outside the city because they generate smoke and noise and are aggressive with the urban environment. This is why it is a model that specialises the urban territory: separate residential and productive spaces are created, and mobility is based on cars so that people can reach these places. However, in the 21st century, the productive units are no longer located outside the city, either because of renewable energies or because the economy and production are based more on information. Therefore, we cannot keep specialising the territory. Urban planning has to change, and in fact it is already changing.

So, what will the city of the future be like?

We have to go back to the compact city, to the Mediterranean city, a city with mixed uses where we can both live and work. It is a dense city because its productive model is a networked model: while the industrial economy was an economy of specialisation, the knowledge economy is an economy of interaction. And social innovation depends on this interaction among people. For this reason, we have to create spaces that encourage this interaction. This is a historical shift which is necessarily being applied in cities all over the world, otherwise they become overwhelmed and inefficient, and since people don’t interact, they are not innovative either.

According to the UN, by 2050 66% of people will live in urban settings. Will the amount of resources and energy needed for urban life increase as well?

Right now, 70% of energy consumption is used for transport. The new city will lower this consumption, because it won’t be larger but denser, and the denser a city is, the less movement and energy consumption. It becomes more efficient. The 20th-century city is not efficient in this sense, because a single person commuting to work by car consumes a huge amount of energy. But if I can walk to work, the worst that can happen is my shoes wear out!

So, do you mean that right now we’re still living in 20th-century cities?

We are at a time of transition. There is global consensus that we have to shift to a 21st-century city model to avoid complete shutdown. For example, I was recently in Lima. It takes three or four hours to get across it, and so the city is constantly enmeshed in traffic jams. The same happens in Bogota, Buenos Aires and Paris. London has a great underground system, but the traffic also grinds to a standstill; this is the reason why the congestion charge is applied to private vehicles if they enter the city centre. So, is this the solution, or should it be a new kind of urban planning focused on ensuring that people can live near where they work? Just like all major changes, this transition poses other problems, like gentrification, which have to be solved through publicly-subsidised housing and rentals for young people, which is not at all easy. And social innovation models also have to be introduced, since the risk of making cities that are not very equitable and socially cohesive is high.

How can urban spaces be improved without breaking their social cohesion?

In the first models we examined, such as Barcelona’s 22@ project, the innovation consisted in integrating the urban planning with the economic strategy. We gradually introduced energy innovations, and now we have introduced the social innovations. But there’s no magic solution. You only see the theory improve through practice and checking the models. And that’s where we are now.

Is all of this related to that concept of “right to the city” which is being discussed again so much recently?

Precisely. A person who is expelled from a neighbourhood because housing prices have increased loses their right to the city, which should be an egalitarian, democratic right. Everyone should have the right to a home and to use public services and spaces. Gentrification is the opposing principle, but it would also be a mistaken not to change the city model, because prices will rise anyhow, plus cities will be brought to the verge of shutdown.

Is 22@ also working on this idea of regaining the public space?

Of course. Urban planning usually sets aside 10% of the land for public space, for streets and other things. However, 22@ sets aside between 30 and 40%. Of this 40%, 10% is green areas and another 10% is public housing. With the 200 total hectares of land in 22@, the entire city gains 60 hectares of public land, which means 600,000 m2 of space for people. And the owners are obligated to set aside this space. The new urban planning has to serve the public interest and be capable of generating spaces for citizens using legal tools.

How can cities take advantage of the new technologies?

Even though I’m an engineer, I’m a bit sceptical of the concept of smart cities and applying the new technologies to urban planning because I think that an overly technological approach makes us lose the sense of serving citizens. The sociologist Richard Sennet wrote a great article explaining that the technological approach to the city has to be based on public service and citizens, not technology. Otherwise, you run the risk of losing sight that the goal is to facilitate citizens’ lives, or of falling into the digital divide because some sectors of the population have difficulties accessing this technology.

To what extent does urban design influence people’s quality of life?

Being able to go to work on foot or using public transport instead of taking your car and spending two hours in a traffic jam is quality of life. Walking in a pleasant environment with public space is quality of life. Driving electric cars which produce less pollution is quality of life. We have to move towards a new city model not only for reasons of economic efficiency but also to improve the daily lives of people, in addition to guaranteeing their personal and professional growth.

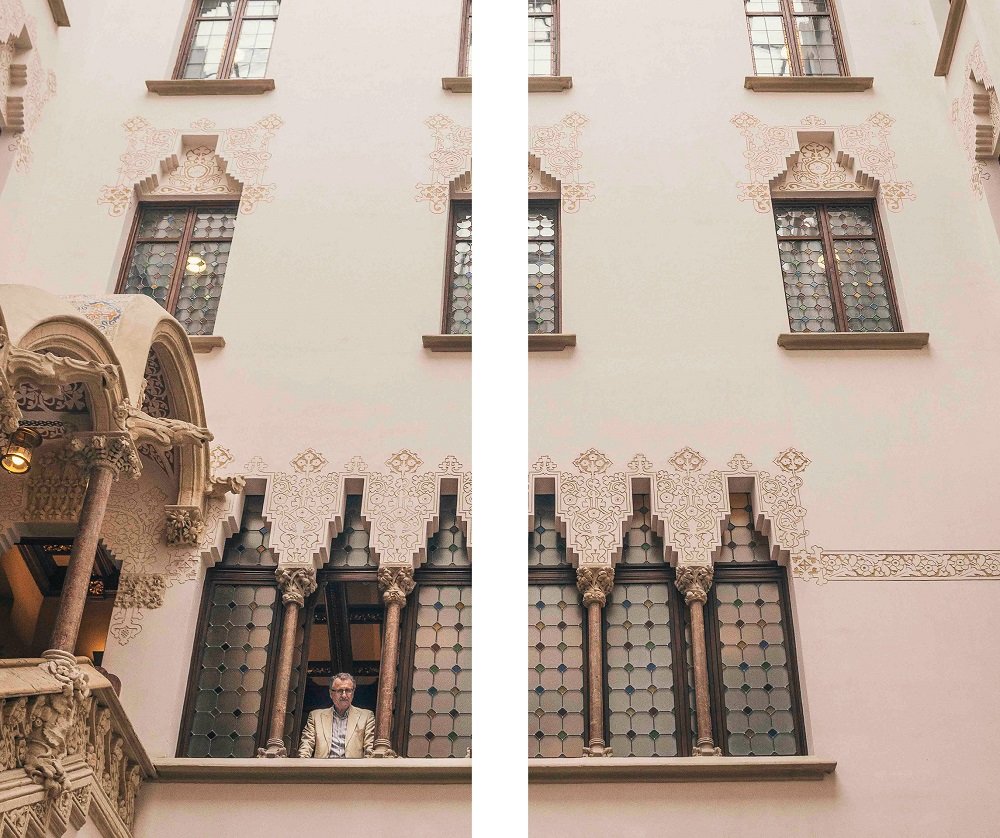

Photograph: Rita Puig-Serra

You can read more stories like this on ALMA, the social social media, a digital space devoted to the social field, which brings a new look at the present and the future of society, from an optimistic and diverse point of view, and from all the initiatives that “la Caixa” Foundation promote.