[dropcap letter=”C”]

lara Wieck Schumann (née Clara Josephine Wieck, Leipzig, 1819 – Frankfurt am Main, 1896) was a German artist who devoted herself to composition and piano interpretation, and that was widely recognized amongst her contemporaries. Sadly, today her name is neither included in the usual repertoire of the most popular concert halls nor in the curricular repertoire of music schools.

Clara’s family life was related to music, earning a living from the concerts given by her mother, Mariane Tromlitz Wieck, recognized and admired pianist, and later the fame as a pedagogue that her father, Friedrick Wieck, received through his wife. Clara’s mother was known for her interpretative talent on the piano, but also for her singing and piano lessons, which gave her an unusual autonomy amongst the young women of the time. In 1823 Mariane left home leaving behind her three children and her furious husband to return the following year, having cultivated her fame throughout Europe. According to the Saxon law of that time, in case of divorce the parents had total custody of the three eldest children, therefore in 1824 when the divorce between Friedrick and Mariane became official, Mariane had to abandon her children; Clara only enjoyed her mother’s company until the age of five.

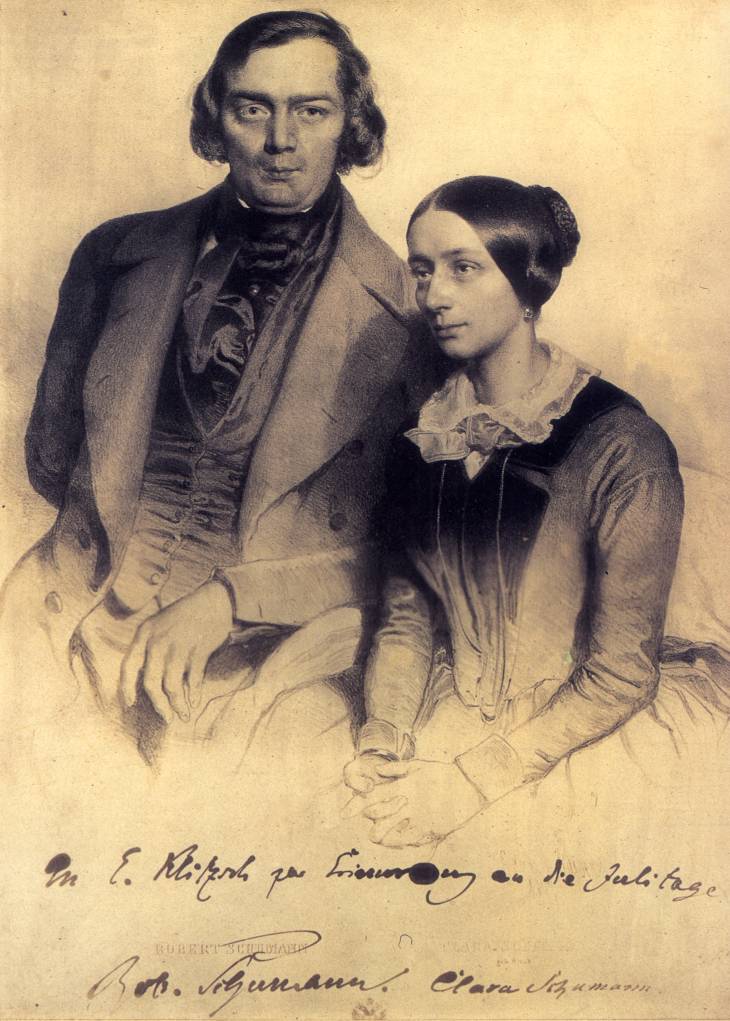

In an environment lacking feminine warmth, Clara began to compose mostly chamber music, and just like other prodigious children of the time she was taken on tour through the European courts, being admired for her fantastic technique. The 1840 she yielded to the wishes of a young Robert Schumann who tended to depression and did not have many financial resources, and she married him. Her father, who did not agree with his daughter’s decision, strongly opposed, a fact that prompted Clara to take her case to court, which ruled in her favour. As a result of this paternal separation Clara recovered contact with her mother, with whom Robert had a very good relationship, and Mariane was able to assist her daughter as mother and grandmother.

“A woman cannot wish to compose, never has a woman been able to do it. Why should I be the first? “

The institutionalized misogyny of the time, which is currently believed to be overcome and accepted, was a constant obstacle in the lives of women (young and not so young) who enjoyed an extraordinary talent, and therefore it is not difficult to guess the relationships that Clara had to keep up with the men who surrounded her intimately and professionally. In fact, one of the composer’s best-known quotes is “I had once believed that I possessed creative talent, but I have dismissed the idea: a woman cannot wish to compose, never has a woman been able to do it. Why should I be the first?”, a hurting reflection that frames the thought of an era and that one cannot see written in male calligraphy. In spite of Clara’s cloudy thoughts, her professional career ended in a way that many would consider brilliant, as a piano teacher at the Frankfurt Conservatoire.

The historical figure of Clara was rediscovered by the musicologists of the nineties, mostly influenced by the so-called “cultural feminism”, and quickly included within the German classical canon to which belong artists like Johannes Brahms, contemporary and intimate friend of her. Despite the obvious importance of Clara Wieck Schumann at historical, cultural and musical level, the current concert halls continue to ignore this figure who, during her lifetime, overcame the fame of her husband and life partner, being the one who interpreted his works due to his fragile health, and the one who contributed the economic resources necessary to survive as a family. In addition, she granted the admiration of some of her most famous contemporaries, such as Brahms, Chopin or Mendelssohn.

In our crucial situation, when young women are asking for equal salaries, are facing and challenging a constant abuse and undervaluation by colleagues, friends, historians and musicologists, it is no longer valid for such transcendental composers as Clara Wieck Schumann to remain part of the shadows’ kingdom. The task of the historians who devoted a large part of their academic life to recovering it from the shelves and the dusty drawers has not been in vain. It is time to include and highlight Clara’s work in the contemporary history of music.