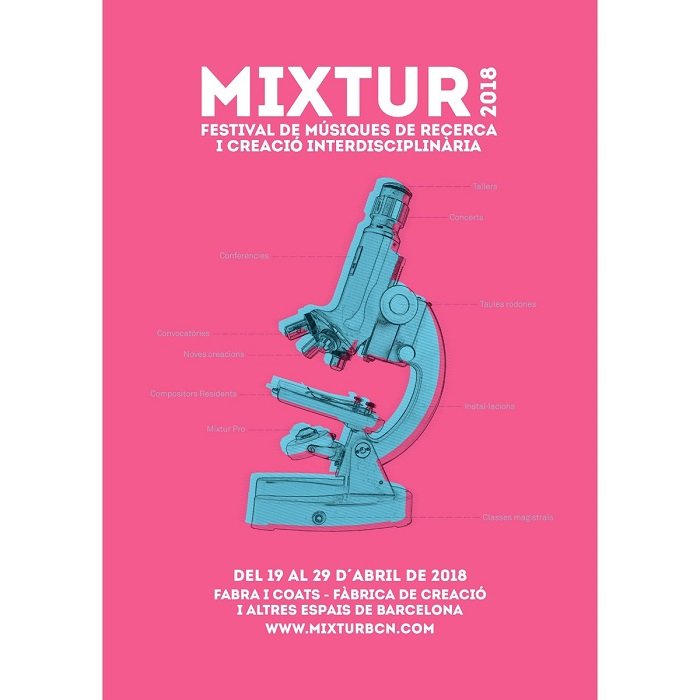

Experimentation, creativity and musical education come together at the Festival Mixtur from 19 to 29 April. In 2017, this festival won the prestigious City of Barcelona award for its commitment to contemporary art. This multi-disciplinary event also incorporates new technology as a vehicle for developing artistic languages, in line with its non-conformist viewpoint and openness towards new ways of experimenting with sound. Concerts and educational activities are held at the former Fabra i Coats factory, including training workshops for musicians and panel discussions led by guest artists, which in this edition include Ricardo Descalzo, Rebecca Saunders and Fred Frith.

The history of this radically current music, which is not only for the enjoyment of those well versed in this subject but also those interested in the latest trends in creativity, goes back to the revolution of the vanguards, which in true post-romantic fashion dared to question the well-beaten path of tradition with a new radicalness. If the gravitational pull of a dominant note in composing moving and familiar melodies was already destroyed by dodecaphony, scientific progress would make another sort of emotional evocation possible. The natural desire to experiment inherent in some composers, such as Edgar Varèse, Karlheinz Stockhausen or Pierre Boulez, seeks to impact states of awareness and perception of sound, taking on the baggage of the most innovative compositions of the first decades of the past century, by what was known as the Second Viennese School (Schoenberg, Berg and Webern).

Perhaps it isn’t a coincidence, given such ambivalence, that mathematical control of sound and a liking for randomness still co-exist to this day, in the way musicians should perform the music

The origins of this new way of composing can be seen in the musical intuitions of an earlier composer, Gustav Mahler. His work brings together the explicit and subliminal interference of sounds, collage, over-use of instruments and the transmutation of genres under the framework of the symphony, which itself represents a world of constant change. A world that includes both the lowest and loftiest, and that blurs the lines between the two, even incorporating the paradoxical mark of something like silence through masses of subtly moving sound, which creates the sensation of an absolute but paradoxically dynamic silence. Consider the beginning of his first symphony or the adagio of his unfinished tenth: the growth, the evolution of the materials is calculable, even though they seem to sink into the verbalisation of an unspeakable truth. Of Webern, Eugenio Trías wrote, “The duality (rational/irrational) of music, the art of madness and ecstasy, but also of numbers and rhythm, is precisely what characterises its essence.”

Perhaps it isn’t a coincidence, given such ambivalence, that mathematical control of sound and a liking for randomness still co-exist to this day, both in the way musicians should perform the music, from Charles Ives to Witold Lutoslawski, to the sound produced, that emanating from the piano prepared by John Cage. The repetition of cells is perpetuated with an attractive degree of unpredictability in Morton Feldman, Steve Reich and Philip Glass. Superimposed melody lines on a loop, not always created electronically (the Kronos Quartet, a string group, is perhaps the most committed to this style of music), contrasts with the minimalism and the presence of silence, also evoked by Arvo Pärt. The work of these creators has inspired, to different extents and fortunes, that of Max Richter, Johann Johannsson, Bryce Dressner, Nico Muhly and Olafur Arnalds, some of whom have now been taken on by classic record labels like Deutsche Grammophon.

Thinking in terms of musical archaeology, even before these new visions that reconcile classical tradition and technical breakthroughs, at times incorporating jazz (listen to Uri Caine or the young Francesco Tristano), the truth is that the invention of electronically controlled instruments was, in its day, a relationship with sound that, in a somewhat Gattopardian way, inverted the terms to preserve its essence. Far from seeking out tonal recreation (traditional harmony) for mere recognition and enjoyment, they created instruments that produced a previously unheard reality. The theremin (1920) and the ondes Martenot (1928), predecessors of today’s electro-acoustic music, create a physical reality (vibrations of waves through amplification) that opens doors to artful manipulation and creation of a sound space. Some pop artists have also followed in this line, including Icelandic creator Björk.

In the end, it is all variations on the fertile questioning of the natural/artificial dichotomy, in line with the suggestions of musique concrète, with the ground-breaking Concert de bruits by Pierre Schaeffer, broadcast on the radio in 1948. Beyond the outrageousness of experimenting, recording and re-organising sounds from daily life, this piece kicked off a time of rare productivity, using synthesisers and samplers. The possibilities for modifying the sound creation (whether mathematically premeditated or improvised, in a studio or live) are endless, and the field for experimentation and learning is totally open under the framework of a festival that has become a benchmark: Mixtur.