[dropcap letter=”J”]

ust five years ago, almost no one had heard of the Societats Anònimes Cotitzades d’Inversions en el Mercat Immobiliari—listed public limited companies for investment in the real estate market, or SOCIMIs. Today they rule the resurgent bricks-and-mortar industry in Spain, with billions in assets, almost exclusively to make significant investments in a business that was synonymous with ostracism and bankruptcy a very short time ago. Their importance has become so great that the SOCIMIs have even managed to get involved in the negotiations between the Spanish government and left-wing Podemos on Spain’s 2019 Budget. The leftist party demanded a change in the tax status of these investment companies—currently exempt from corporation tax—which they accuse of having a major role in increasing rents. But why have they become the crown jewels of the property market in so little time?

In 2013 the scenario changes, the real estate sector has hit rock bottom, the banks have recovered thanks to the €60bn bailout, and the most toxic assets have gone to the SAREB bad bank. On this basis, Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy’s new Partido Popular government decides to give SOCIMIs a fresh opportunity

Let’s go back to 2009. The Spanish economy is immersed in one of the worst crises in recent history and it’s property, until recently the spearhead of the “Spanish miracle,” that’s sinking fast. The then Prime Minister, Socialist José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, passes a law to create a domestic version of what is known throughout the world as REITs (Real Estate Investment Trusts), created in the United States as financial vehicles to channel real estate investment through companies that are listed on the stock market. The business is simple, invest in property, from offices and industrial buildings to hotels and homes, and manage them for rental.

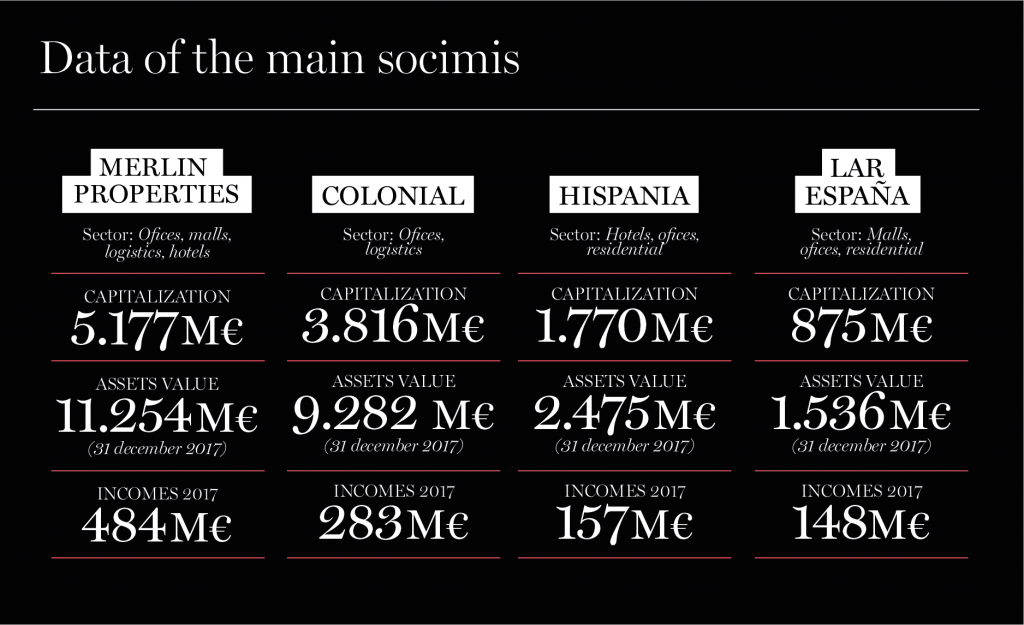

The invention, however, does not gel. The bricks-and-mortar industry is too weak to generate business and the only ones who dare stick their fingers in the pie at that moment are the vulture funds. What’s more, listing on the stock market in the midst of the global financial chaos does not look like great idea. But in 2013 the scenario changes, the real estate sector has hit rock bottom, the banks have recovered thanks to the €60bn bailout, and the most toxic assets have gone to the SAREB bad bank. On this basis, Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy’s new Partido Popular government decides to give SOCIMIs a fresh opportunity, relaxing requirements and establishing the tax regime—now being questioned—in order to encourage investors to join in the game. It works, and boy does it work: five years later, the four main SOCIMIs—Merlin, Colonial, Hispania and Lar España—garner over 27 billion in assets in the market.

The sector argues that the main value of SOCIMIs is precisely that they provide the rental business with transparency and that these big proprietors invest to keep their flats in peak condition to prevent them from losing value

For Sergio Espadero, the director of Advisory Services at consultants Gesvalt, the rapid growth of these companies can be explained by what they have been able to contribute as a stimulant for the Spanish property market: “They have provided professionalism, dynamism and transparency in the sector, and growth in investment. On the other hand, they cover a current need in the Spanish real estate market, which is the professional management of rental housing.” In this sense, Espadero says it is inappropriate to say that SOCIMIs are contributing to the rise in rental prices because the approximately 20,000 homes that they have in their portfolio represent, he argues, less than 5% of the total rental pool. In fact the sector argues that the main value of SOCIMIs is precisely that they provide the rental business with transparency and that these big proprietors invest to keep their flats in peak condition to prevent them from losing value, a function individual owners who place their flats on the rental market do not, or cannot, always perform.

[separator type=”thin”]

THE STAKE TO GET OUT OF THE HOLE

In 2013, the Rajoy Government approved amendments to certain main requirements for the SOCIMI regime the Zapatero socialist government had approved a few years earlier. This included lowering the minimum starting capital from €15 million to €5 million, and allowed them to be listed on the MAB Alternative Stock Market, where the information requirements are less strict than in the Spanish Stock Exchange’s general trading system, and with lower trading costs. The minimum life of the investment was reduced from five years to three, and the corporation tax exemption was established—although shareholders are required to pay tax on dividends—including a 95% discount granted on taxes derived from the sale of real estate (Stamp Duty and Property Transfer Tax). It was a way of making the property market attractive to foreign investors, the stake to get out of the hole.

[separator type=”thin”]

And the SOCIMIs go well beyond the residential market. Today there are some forty of these types of companies listed on the Spanish stock market, most through the MAB, the Mercat Alternatiu Borsari or Alternative Stock Market, where SOCIMIs make up almost half of the market’s total capitalization. A large part of the investors behind these corporations are international funds—about 50%, capital that was attracted to the Spanish real estate market by the conditions approved for the SOCIMIs, but that would have gone to other markets had it not been for this regime. At least that is what the CEO of Merlin (the queen of SOCIMIs), Ismael Clemente explained recently. The executive called to mind that these societies “have brought in €20 billion in capital,” pointing out that if the Spanish real estate sector has been able to raise its head again, it has been thanks to this stimulus.

The truth is that SOCIMIs are backed by institutional investors and professionals interested in juicy dividends—SOCIMIs are obliged by law to pay shareholders annually—but unlike vulture funds, their business model is not based on buying cheap, expecting to sell later at a profit. What counts here is profits obtained from sustained operation of rental assets.

The new queens of the real estate market are unlike those clay-footed giants of the property bubble years, like Martinsa-Fadesa, Astroc, or Habitat, and are a long way from contractor Francisco “El Pocero” Hernando’s ghost developments in Seseña, south of Madrid. Espadero explains that SOCIMIs “bring transparency and traceability to management,” and he emphasizes that beyond the tax advantages, their success is also due to the advantages for their shareholders: “Real estate assets are transposed as listed shares in a vehicle that allows total or partial liquidity of an asset, without the need for overall investment or divestment.” That is why Espadero is convinced that SOCIMIs “have come to stay as the chief players in the Spanish real estate market.”

According to Gesvalt, 70.52% of the assets in the portfolios of Spanish SOCIMIs are concentrated in the residential sector, although if they are calculated by asset value, homes do not reach 50% of the total. Shopping centres, offices, warehouses and logistics, and commercial premises… The list of the investment profile that completes the portfolio of assets is very varied and, although for the time being the same fund may have interests in different sectors, analysts expect the trend in the coming years will be for concentration and specialization. But on the path towards consolidation, the sector is watching the pressures for change in the SOCIMIs’ tax regime closely. For Espadero, if an agreement is finally reached to eliminate the tax advantages, the price to pay will be very high: “This will definitely affect the credibility of Spain again, because in its day international funds were invited to come to Spain under a REIT-type regime, standard in other countries, and if there is now an alteration of the tax system, the dependability of the country’s fiscal and legal decisions would be questioned,” he emphasizes.