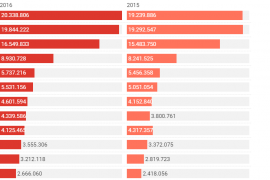

Barcelona, with 20.33 million overnight stays, led in 2016 the...

Entrepreneurs' Organization promotes entrepreneurship in community and from a holistic...

Take a deep breath. Alright? We are going to talk...

A longer life expectancy throughout the planet is something that...

In hospitals, besides managing health, they manage life and death...

CosmoCaixa commemorates the half century of the arrival to the...

The Catalan seed company invoices 64% of turnover through exports,...

Experiencing a match day in the Wanda Metropolitano Stadium allows...

A tree in the city is much more than ornamentation...

"Mirrors, inside and outside of reality" is one of the...

Música clásica sobre la arena de la playa en dos...

The first session of the cycle on the regatta organized...

The hospital's managing director, Manel del Castillo, and the pharmaceutical...

Generalitat y Ayuntamiento impulsarán dos equipamientos de 'Casa de les...

Leticia Beleta, director of Alexion Pharmaceuticals in Spain and Portugal,...

We all have a friend who never leaves the Gràcia...

Barcelona director opts for Best International Film with 'La sociedad...

The hotel and industrial sectors softened the market's decline last...

The technology company, with a workforce of 35 employees and...

“The women of yesteryear were strong and had to fight...

“Tokyo is a collection of villages,” said Junichiro Tanizaki, author of In Praise of Shadows, among other works.

But, like an octopus spreading its tentacles, the many train networks and twelve metro lines, together, serve more than eight million users each day. Here it’s common for everything to revolve around the rails. Tokyoites spend two hours a day, on average, on some sort of train, commuting to and from work, school, shopping or parks, like the famous Ueno park when the Sakura festival arrives and everyone goes out for a picnic and to watch the cherry blossoms. Visitors are impressed with the orderly way the human mass moves, for example, at the station in Shinjuku (with its throng of skyscrapers built to withstand earthquakes and the headquarters of the municipal government), the order and relative silence with which everything goes on in the corridors and on the platforms. The cleanliness of these high-traffic areas is also quite surprising. Neighbourhoods like Shibuya, one of the favourites among young people, with its monument to the famous Hachiko dog, a perfect meeting point, who died instead of moving from the spot where it was waiting for its master.

Old Edo, now Tokyo, which means ‘eastern capital’, became the capital in 1868 when the imperial court moved from Miyako, current-day Kyoto, to the banks of this great bay that, like a shell, embraces the waters of that part of the Pacific Ocean.

When leaving any of the dozens of exits at these large stations, some taking you directly into large department stores, there is always a swarm of small shops and restaurants of all types. Or taxi ranks, with drivers normally wearing white gloves, doors that open automatically and white-lace covers on the seats. Under the rail bridges you find the best yakitori (skewers), sushi, sashimi, sukiyaki, udon and soba, along with the many other types of noodles, all with great sake, which is served warm, or beer. Not to mention that the culinary delights here include all sorts of cuisines, with dishes often on display in restaurant windows – plastic copies identical to the ones diners will be served. And always careful not to miss the last train or metro before reaching the final destination, where the problem is finding your bike to cycle home, depending on how much alcohol has been drunk after the long work day. Bathing in the furo, with water nearly boiling, and ready to do it all over again first thing the next morning. This is life for millions of people living in greater Tokyo, which covers nearly half the rim of the bay, from Yokohama in the south to Chiba in the west.

Old Edo, now Tokyo, which means ‘eastern capital’, became the capital in 1868 when the imperial court moved from Miyako, current-day Kyoto, to the banks of this great bay that, like a shell, embraces the waters of that part of the Pacific Ocean. The bay commodore Perry’s warships sailed into, when the nascent colonial power of the United States began to impose their rules on half the world. This is how the feudal Tokugawa shogunate came to an end, giving rise to the modernisation of the country during the time of the Meiji Emperor, and the origin of the continued growth of the Japanese metropolis.

From Tokyo station, development began on one of the most complex rail networks in the world, connecting to the rest of the country (the Shinkansen or bullet train has been running since 1964), as well as a circular metropolitan rail line, the Yamanote line, which united areas where villages became cities within the metropolitan area.

It was around the imperial palace where the Emperor lives with his court, a walled oasis of gardens protected by a moat, where this city without a centre began to grow, the neighbourhoods expanding out in concentric circles like the trunk of a huge cedar tree. In the late 19th century of our era (in Japan the years are numbered in the era of each emperor), Tokyo already had three million inhabitants and was relatively open to foreign influences, after many centuries locked away, with European influence in that industrial revolution sparking the Japanese economic empire. Near the large esplanade, at the main entrance to the palace, the Tokyo rail station was built and, around it, the neighbourhood of Maronouchi to house the government and headquarters of thriving companies. The area conserves this essence today, with the National Diet, the parliament, and the home of the prime minister. As well as bank headquarters, shopping centres and the emblematic Imperial hotel, still the chosen site for elite social events. From Tokyo station, development began on one of the most complex rail networks in the world, connecting to the rest of the country (the Shinkansen or bullet train has been running since 1964), as well as a circular metropolitan rail line, the Yamanote line, which united areas where villages became cities within the metropolitan area: Akihabara, Ueno, Otsuku, Shinjuko, Harjuko, Shibuya, Meguro, Kita-Shinabara, Hamucho and Shimbashi, to name the most important ones.

It’s not all work for Tokyoites, although pressure and competitiveness are a way of life. When Sunday rolls around, as it is still quite common to work at least Saturday morning, it is time for shopping (to the Akihabara neighbourhood if you’re looking for the latest in technology), recreation or just staying home and resting. Tokyo has several huge parks for leisure activities. At some, like Yoyogi Park (with facilities from the 1964 Olympics updated for the upcoming 2020 games, and more), you’re sure to get a good show. Here, anyone can set up their own dance or music show, or anything else to blow off steam built up over the long week. Near Yoyogi Park are the Meiji gardens and temple, huge and shrouded in peace and quiet for the soul. A good place to see a wedding or lovely Japanese women dressed in traditional kimonos. And, in terms of temples, which can be found in many neighbourhoods, both Shinto (Japan’s own religion) and Buddhist, the Kannon temple is not to be missed. Here the Japanese purify themselves with incense smoke after crossing an avenue full of souvenir shops, with fans, cookies and umbrellas. For the Japanese, it is almost obligatory to go to temple on New Year’s Day and buy an arrow to put in the fire and make a wish for the new year. And for this, they don’t follow the imperial calendar but the universal Gregorian calendar.

Going to see kabuki, the Japanese national theatre, is another way to see popular culture with their all-male cast, playing both men and women. The shows last hours and are held throughout the day, with the audience yelling, applauding and eating depending on what is happening. And for the more refined, there is Noh theatre, where just moving an arm, for example, can take minutes and be done in absolute silence. Among the curiosities in Tokyo is Tsukiji market, the largest fish market in the world, where the steam coming off the frozen tuna (some of which are auctioned off for tens of thousands of euros) and the variety of fish and seafood on offer are part of the show. You have to go very early in the morning and be ready to be shoved around by professional buyers who don’t always have the same tastes as the gate-crashing visitors. A market that is going extinct, because it will soon be moved to make room for Olympic venues. I also recommend visiting the Tokyo National Museum, the oldest in the country, in Ueno park, which is a good introduction to sophisticated Japanese culture. And, to better understand World War II, you have to go to the Yasukuni Shinto shrine, which honours the soldiers who died in battle (with the ongoing controversy of including those who were tried and executed as war criminals), as well as the associated museum, which even has a kamikaze statue.

To live in Tokyo, it’s best not to be prone to heart disease. Because earthquakes are common. If there’s one during the day and you’re on the street or the train, often times you don’t even notice it. But at night, if the shaking is vertical or starts to rattle the glass in the cupboards, it’s best to give yourself over to God, or Buddha.

Crossing the Rainbow bridge takes you towards the centre of Tokyo Bay, where feats of engineering have taken land from the sea in Odaiba. Here, like an island in the middle of the bay, the sea air bathes shopping centres and a hive of restaurants, bars and discos. For young Tokyoites, it is the final frontier of modernity. And, for some of the best views of the unattainable vision of the Tokyo metropolis, there’s nothing better than going up to the top floor of Roppongi Hills, one of the classic night-life neighbourhoods with its restaurant/look-out point with views, pollution allowing, of the snowy peak of Mount Fuji, Japan’s national icon.

To live in Tokyo, it’s best not to be prone to heart disease. Because earthquakes are common. If there’s one during the day and you’re on the street or the train, often times you don’t even notice it. But at night, if the shaking is vertical or starts to rattle the glass in the cupboards, it’s best to give yourself over to God, or Buddha. In the end, you get used to it. Although it always reminds you that the city is right on the fault line and that 14,000 people died in the horrible 1923 quake, including the victims of the fires the earthquake caused in a city that was mainly built of wood. This fire destruction was on par with what Tokyoites suffered in the intense bombing by the US army in the final days of WWII, before putting an end to Japan’s bellicose imperialism by dropping atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945. This was when the Japanese first heard Emperor Hirohito’s voice, who they considered a heavenly being, reading the surrender speech on NHK public radio. From those ashes and with their tenacity, the Japanese rebuilt Tokyo.

As only the large avenues have names, getting around the back streets in Tokyo, labelled by chome (small district) and house number, is an experience that develops the visual memory. A petrol station, a convenience store, a clothes store or a bookshop are always used as references in locating an address. If you go to someone’s house, the invitation always comes with a mini-map with the metro station and some landmarks you’ll pass on the way, if you make it. You can always stop and ask. Even if your language skills are rudimentary, you’ll find people willing to help, although sometimes with contradictory directions. Tokyo, which has it all, even an identical scale model of the Eiffel Tower in Paris, is a city of cities, full of such peculiar contrasts that it leaves no one indifferent. You either love Tokyo or you hate it, but it is always surprising. It’s a bit like a voyage to another planet.

“Tokyo is a collection of villages,” said Junichiro Tanizaki, author of In Praise of Shadows, among other works.

But, like an octopus spreading its tentacles, the many train networks and twelve metro lines, together, serve more than eight million users each day. Here it’s common for everything to revolve around the rails. Tokyoites spend two hours a day, on average, on some sort of train, commuting to and from work, school, shopping or parks, like the famous Ueno park when the Sakura festival arrives and everyone goes out for a picnic and to watch the cherry blossoms. Visitors are impressed with the orderly way the human mass moves, for example, at the station in Shinjuku (with its throng of skyscrapers built to withstand earthquakes and the headquarters of the municipal government), the order and relative silence with which everything goes on in the corridors and on the platforms. The cleanliness of these high-traffic areas is also quite surprising. Neighbourhoods like Shibuya, one of the favourites among young people, with its monument to the famous Hachiko dog, a perfect meeting point, who died instead of moving from the spot where it was waiting for its master.

Old Edo, now Tokyo, which means ‘eastern capital’, became the capital in 1868 when the imperial court moved from Miyako, current-day Kyoto, to the banks of this great bay that, like a shell, embraces the waters of that part of the Pacific Ocean.

When leaving any of the dozens of exits at these large stations, some taking you directly into large department stores, there is always a swarm of small shops and restaurants of all types. Or taxi ranks, with drivers normally wearing white gloves, doors that open automatically and white-lace covers on the seats. Under the rail bridges you find the best yakitori (skewers), sushi, sashimi, sukiyaki, udon and soba, along with the many other types of noodles, all with great sake, which is served warm, or beer. Not to mention that the culinary delights here include all sorts of cuisines, with dishes often on display in restaurant windows – plastic copies identical to the ones diners will be served. And always careful not to miss the last train or metro before reaching the final destination, where the problem is finding your bike to cycle home, depending on how much alcohol has been drunk after the long work day. Bathing in the furo, with water nearly boiling, and ready to do it all over again first thing the next morning. This is life for millions of people living in greater Tokyo, which covers nearly half the rim of the bay, from Yokohama in the south to Chiba in the west.

Old Edo, now Tokyo, which means ‘eastern capital’, became the capital in 1868 when the imperial court moved from Miyako, current-day Kyoto, to the banks of this great bay that, like a shell, embraces the waters of that part of the Pacific Ocean. The bay commodore Perry’s warships sailed into, when the nascent colonial power of the United States began to impose their rules on half the world. This is how the feudal Tokugawa shogunate came to an end, giving rise to the modernisation of the country during the time of the Meiji Emperor, and the origin of the continued growth of the Japanese metropolis.

From Tokyo station, development began on one of the most complex rail networks in the world, connecting to the rest of the country (the Shinkansen or bullet train has been running since 1964), as well as a circular metropolitan rail line, the Yamanote line, which united areas where villages became cities within the metropolitan area.

It was around the imperial palace where the Emperor lives with his court, a walled oasis of gardens protected by a moat, where this city without a centre began to grow, the neighbourhoods expanding out in concentric circles like the trunk of a huge cedar tree. In the late 19th century of our era (in Japan the years are numbered in the era of each emperor), Tokyo already had three million inhabitants and was relatively open to foreign influences, after many centuries locked away, with European influence in that industrial revolution sparking the Japanese economic empire. Near the large esplanade, at the main entrance to the palace, the Tokyo rail station was built and, around it, the neighbourhood of Maronouchi to house the government and headquarters of thriving companies. The area conserves this essence today, with the National Diet, the parliament, and the home of the prime minister. As well as bank headquarters, shopping centres and the emblematic Imperial hotel, still the chosen site for elite social events. From Tokyo station, development began on one of the most complex rail networks in the world, connecting to the rest of the country (the Shinkansen or bullet train has been running since 1964), as well as a circular metropolitan rail line, the Yamanote line, which united areas where villages became cities within the metropolitan area: Akihabara, Ueno, Otsuku, Shinjuko, Harjuko, Shibuya, Meguro, Kita-Shinabara, Hamucho and Shimbashi, to name the most important ones.

It’s not all work for Tokyoites, although pressure and competitiveness are a way of life. When Sunday rolls around, as it is still quite common to work at least Saturday morning, it is time for shopping (to the Akihabara neighbourhood if you’re looking for the latest in technology), recreation or just staying home and resting. Tokyo has several huge parks for leisure activities. At some, like Yoyogi Park (with facilities from the 1964 Olympics updated for the upcoming 2020 games, and more), you’re sure to get a good show. Here, anyone can set up their own dance or music show, or anything else to blow off steam built up over the long week. Near Yoyogi Park are the Meiji gardens and temple, huge and shrouded in peace and quiet for the soul. A good place to see a wedding or lovely Japanese women dressed in traditional kimonos. And, in terms of temples, which can be found in many neighbourhoods, both Shinto (Japan’s own religion) and Buddhist, the Kannon temple is not to be missed. Here the Japanese purify themselves with incense smoke after crossing an avenue full of souvenir shops, with fans, cookies and umbrellas. For the Japanese, it is almost obligatory to go to temple on New Year’s Day and buy an arrow to put in the fire and make a wish for the new year. And for this, they don’t follow the imperial calendar but the universal Gregorian calendar.

Going to see kabuki, the Japanese national theatre, is another way to see popular culture with their all-male cast, playing both men and women. The shows last hours and are held throughout the day, with the audience yelling, applauding and eating depending on what is happening. And for the more refined, there is Noh theatre, where just moving an arm, for example, can take minutes and be done in absolute silence. Among the curiosities in Tokyo is Tsukiji market, the largest fish market in the world, where the steam coming off the frozen tuna (some of which are auctioned off for tens of thousands of euros) and the variety of fish and seafood on offer are part of the show. You have to go very early in the morning and be ready to be shoved around by professional buyers who don’t always have the same tastes as the gate-crashing visitors. A market that is going extinct, because it will soon be moved to make room for Olympic venues. I also recommend visiting the Tokyo National Museum, the oldest in the country, in Ueno park, which is a good introduction to sophisticated Japanese culture. And, to better understand World War II, you have to go to the Yasukuni Shinto shrine, which honours the soldiers who died in battle (with the ongoing controversy of including those who were tried and executed as war criminals), as well as the associated museum, which even has a kamikaze statue.

To live in Tokyo, it’s best not to be prone to heart disease. Because earthquakes are common. If there’s one during the day and you’re on the street or the train, often times you don’t even notice it. But at night, if the shaking is vertical or starts to rattle the glass in the cupboards, it’s best to give yourself over to God, or Buddha.

Crossing the Rainbow bridge takes you towards the centre of Tokyo Bay, where feats of engineering have taken land from the sea in Odaiba. Here, like an island in the middle of the bay, the sea air bathes shopping centres and a hive of restaurants, bars and discos. For young Tokyoites, it is the final frontier of modernity. And, for some of the best views of the unattainable vision of the Tokyo metropolis, there’s nothing better than going up to the top floor of Roppongi Hills, one of the classic night-life neighbourhoods with its restaurant/look-out point with views, pollution allowing, of the snowy peak of Mount Fuji, Japan’s national icon.

To live in Tokyo, it’s best not to be prone to heart disease. Because earthquakes are common. If there’s one during the day and you’re on the street or the train, often times you don’t even notice it. But at night, if the shaking is vertical or starts to rattle the glass in the cupboards, it’s best to give yourself over to God, or Buddha. In the end, you get used to it. Although it always reminds you that the city is right on the fault line and that 14,000 people died in the horrible 1923 quake, including the victims of the fires the earthquake caused in a city that was mainly built of wood. This fire destruction was on par with what Tokyoites suffered in the intense bombing by the US army in the final days of WWII, before putting an end to Japan’s bellicose imperialism by dropping atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945. This was when the Japanese first heard Emperor Hirohito’s voice, who they considered a heavenly being, reading the surrender speech on NHK public radio. From those ashes and with their tenacity, the Japanese rebuilt Tokyo.

As only the large avenues have names, getting around the back streets in Tokyo, labelled by chome (small district) and house number, is an experience that develops the visual memory. A petrol station, a convenience store, a clothes store or a bookshop are always used as references in locating an address. If you go to someone’s house, the invitation always comes with a mini-map with the metro station and some landmarks you’ll pass on the way, if you make it. You can always stop and ask. Even if your language skills are rudimentary, you’ll find people willing to help, although sometimes with contradictory directions. Tokyo, which has it all, even an identical scale model of the Eiffel Tower in Paris, is a city of cities, full of such peculiar contrasts that it leaves no one indifferent. You either love Tokyo or you hate it, but it is always surprising. It’s a bit like a voyage to another planet.