In critical times, it is fair to determine the relevance...

Three Catalan restaurants – El Celler de Can Roca (2),...

From the Sociedad Catalana para el Alumbrado por Gas, founded...

The successful Mobile World Congress held recently in Barcelona has...

We are beginning to take in that it is possible...

“Science is alive and it’s part of culture. Science is...

After 137 years of history, the Catalan company of pyrotechnics...

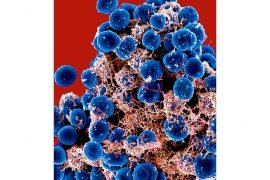

Fatigue, vomiting, hair loss... We have assumed that, to be...

Hollywood has taught that three possible destinations await humanity: fighting,...

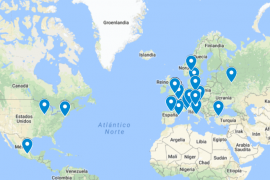

There is no need, anymore, to go to Silicon Valley...

Música clásica sobre la arena de la playa en dos...

The first session of the cycle on the regatta organized...

The hospital's managing director, Manel del Castillo, and the pharmaceutical...

Generalitat y Ayuntamiento impulsarán dos equipamientos de 'Casa de les...

Leticia Beleta, director of Alexion Pharmaceuticals in Spain and Portugal,...

We all have a friend who never leaves the Gràcia...

Barcelona director opts for Best International Film with 'La sociedad...

The hotel and industrial sectors softened the market's decline last...

The technology company, with a workforce of 35 employees and...

“The women of yesteryear were strong and had to fight...

[dropcap letter=”O”]

n February 10, the philosopher from Barcelona Eugenio Trías (1942-2013) had been missing for five years. Trías truly loved Barcelona; like Woody Allen loved New York or Lawrence Durrell loved Alexandria. In fact, his first inquiries into Platonic thought -in search of an eros that tends to rise to the Ideas, to the general and clear vision of truth, posited in Banquete- have to be complemented, in his opinion, with the vision of the architect, the sculptor. In short, the artist who descends from the contemplation of ideas to shape the city, to build public spaces, to translate the vision to which eros has transported him into work, into stone, into painting.

-Oh! detura’t un punt! Mira el mar, Barcelona,

com té faixa de blau fins al baix horitzó,

els poblets blanquejant tot al llarg de la costa,

que se’n van plens de sol vorejant la blavor.

I tu fuges del mar?..-Vinc del mar i l’estimo,

i he pujat aquí dalt per mirar-lo millor,

i me’n vaig i no em moc: sols estenc els meus braços

perquè vull Catalunya tota a dintre el meu cor.Joan Maragall, Oda nova a Barcelona

It is in The Artist and the City (1974) where Trías tells us about the connection between eros and poiesis, between desire and production; where he expresses the need for philosophical search to culminate in civic action, in the configuration of the city. The interaction between the philosopher and the city will also be reflected in his memoir, The Tree of Life (2003). There he tells us about his childhood escapades through the streets of Barcelona, holding his grandmother’s hand, who was of Ecuadorian descent, visiting the most emblematic museums and places in the city, which would forge his imagination. There are constant references to his walks through the Eixample neighbourhood, his visits to the Palau de la Música to listen to the great Eduard Toldrà, his pilgrimage through all the city’s cinemas, his visits to the Barceloneta, his night walks to the Tibidabo and the view of the city at his feet. Later on he will experience the longing, when in Germany, for Barcelona’s blue sky.

A PHILOSOPHY AT THE SERVICE OF THE CITY

His well-known philosophy of the limit, which conceives the human being as an “inhabitant of the frontier” -the zone that joins the frame of appearing, that of visible reality and an hermetic enclosure, that of mystery- would never be a solipsistic exercise, closed around itself, but fruit of a rich interaction between the thinker and his city. An interaction from which a philosopher’s clear awareness of public vocation is born, and consequently his eagerness to shape his city, to produce beautiful work in it which invites observers to think and reflect. Barcelona is so present in his work, that in his book City over City (2001) it can be guessed between the lines. There he conceives his philosophy like an ideal city, formed by four neighbourhoods: philosophical, ethical, artistic and religious. An ideal city that interacts with the real city.

“A visible city supported by submerged, buried, labyrinthine cities, representing the different strata of cities superimposed by history”

Trías follows Wittgenstein’s reflections on the conception of human language, understood as a city that amalgamates an old town, reorganized by modern forms of rationalization; or, like Freud, who thought of Rome as a “city over a city”, a visible city supported by submerged, buried, labyrinthine cities, representing the different strata of cities superimposed by history. Trías understands his ideal city as a symbolic model of his beloved Barcelona, inspired in turn by Joseph Rykwert’s analysis of the founding rites of cities in the ancient world.

FROM THE OLD TOWN TO THE EIXAMPLE, THE CLARIFYING MODERNITY

Following that beautiful metaphor, Trías conceives the medieval city -that of the cathedral and the Jewish quarter, of the guilds and craftsmen- as the old town, which hides a religious symbolism. That of cathedral Europe, with its love for stone, verticality and light; with its organic-spiritual conception in the form of an ascending tree, and its spectacular Gothic arches. Without forgetting the powerful Catalan Romanesque, treasured in the MNAC today, with its Pantocrators and mural paintings impregnated with colours that will determine the vision and the imagination of strollers through Barcelona. Trías’ strolling through the medieval city also reveals the Arab and Jewish trace in Barcelona, which speaks of a strange interreligious dialogue: the three great monotheisms of the past were hybridised in fascinating ways, such as the oriental tradition of courtly love, which has shaped the passionate erotic of the Mediterranean man in this part of the world.

This old city centre has been expanded, clarified and complemented by the famous Cerdà plan, with its Ensanche right and left that unite the different original town halls (Gracia, Sarrià, etc.) as a dense mesh, scattered in the true “city of cities” that is Barcelona. Here functionalism, aesthetics, beauty and practicality go hand in hand, configuring a distinctive, characteristic and unmistakable identity. In the same way, Trías always understood Modernity not as an attempt to suppress the symbolic-religious world of the medieval, but as the act of becoming aware, clarifying and elevating the mysterious character of sacred things to transparency. This Modernity that knows how to dialogue with the past, which is projected utopically but with a foundation, is at the heart of Trías’ work, as a result of his relationship with Barcelona.

“Trías always understood Modernity not as an attempt to suppress the symbolic-religious world of the medieval, but as the act of becoming aware, clarifying and elevating the mysterious character of sacred things to transparency”

The “ethical neighbourhood” of which Trías speaks corresponds to the border subject who, in the elevation, rises to hear the imperative voice that commands it to be what it already is: a border subject, one capable of tapping into the village’s endogamous instances and the centrifugal requirements of the global casino, through the awareness of belonging to a civic centre, at the origin of the city.

THE ARCHITECTURAL REVOLUTION AND THE CIVIC SPIRIT

That is why Trías always maintained the dream of that Barcelona, heiress of the different Olympic venues, that knew how to correctly mix tradition and modernity, maintaining the balance between the spirit of the earth and a modernity with a human face. The imprint of the architecture made in the 70s, 80s and 90s in Barcelona -a time when he was a professor at the School of Architecture of Barcelona- shows his interest in the different revolutions in the forms of space and time that the School of Barcelona’s new urbanism introduced. His fine perception for everything that happened in the city in recent decades shows the avant-garde of his philosophical proposal, the clarity of his view on the new conditions of a city in perpetual change, in continuous renewal.

This love for Barcelona is evident in the civic sense that Trías believed to be characteristic of Barcelona, as he shows in his revision of Joan Maragall’s ideas. Trías had the character of a wise man, bourgeois and civic, capable of uniting tradition and modernity and opening himself -with innate interest and curiosity- to new things, without losing the most genuine of his own traditions.

“His love for Barcelona is evident in the civic sense that Trías believed to be characteristic of Barcelona”

For him, a sense of congenital hospitality and a civic love were the best Catalan traits and could be summarised in Barcelona’s citizens. He believed in Maragall’s “Ode to Barcelona”, which called for coexistence among all the classes and strata that make up the city and established the ethical-linguistic capacity to ask for and give forgiveness, as the identifying attribute of those who have a conscience. In civic terms, the dream of a global vision, of a Promethean and inhuman nature -perhaps the dream that took hold in the 20s and 30s of certain megalomaniac projects during the expansion of New York- was to give way to a human and cordial labyrinthine city like Barcelona.

THE MARITIME BARCELONA, A BORDER CITY

Perhaps because he was born at a time when Barcelona lived with “its back to the sea”, there is no reference to Barcelona’s maritime character in his work. However, I think that his formulation of the border character of the human condition is best reflected in Barcelona, a Mediterranean city. Trías always loved the sea, marine life, as he was also an exquisite gourmet (seafood, paellas, fish stews), and a regular visitor of the Barceloneta.

His greatest pleasure was walking down to the sea, where the Universitat Pompeu Fabra is located. Then walking down the new seafront promenades, built for the Olympic games of 1992, and having lunch in front of the sea. The sea is the perfect symbol of the limit that unites and separates two shores: that of the known and that of the unknown. A Barcelona projected towards the sea in a conflictive relationship with it is the living and real figure of its border condition, the central core of the thought of one of the great philosophers of the 20th century, who was undoubtedly an eminent man from Barcelona.

[dropcap letter=”O”]

n February 10, the philosopher from Barcelona Eugenio Trías (1942-2013) had been missing for five years. Trías truly loved Barcelona; like Woody Allen loved New York or Lawrence Durrell loved Alexandria. In fact, his first inquiries into Platonic thought -in search of an eros that tends to rise to the Ideas, to the general and clear vision of truth, posited in Banquete- have to be complemented, in his opinion, with the vision of the architect, the sculptor. In short, the artist who descends from the contemplation of ideas to shape the city, to build public spaces, to translate the vision to which eros has transported him into work, into stone, into painting.

-Oh! detura’t un punt! Mira el mar, Barcelona,

com té faixa de blau fins al baix horitzó,

els poblets blanquejant tot al llarg de la costa,

que se’n van plens de sol vorejant la blavor.

I tu fuges del mar?..-Vinc del mar i l’estimo,

i he pujat aquí dalt per mirar-lo millor,

i me’n vaig i no em moc: sols estenc els meus braços

perquè vull Catalunya tota a dintre el meu cor.Joan Maragall, Oda nova a Barcelona

It is in The Artist and the City (1974) where Trías tells us about the connection between eros and poiesis, between desire and production; where he expresses the need for philosophical search to culminate in civic action, in the configuration of the city. The interaction between the philosopher and the city will also be reflected in his memoir, The Tree of Life (2003). There he tells us about his childhood escapades through the streets of Barcelona, holding his grandmother’s hand, who was of Ecuadorian descent, visiting the most emblematic museums and places in the city, which would forge his imagination. There are constant references to his walks through the Eixample neighbourhood, his visits to the Palau de la Música to listen to the great Eduard Toldrà, his pilgrimage through all the city’s cinemas, his visits to the Barceloneta, his night walks to the Tibidabo and the view of the city at his feet. Later on he will experience the longing, when in Germany, for Barcelona’s blue sky.

A PHILOSOPHY AT THE SERVICE OF THE CITY

His well-known philosophy of the limit, which conceives the human being as an “inhabitant of the frontier” -the zone that joins the frame of appearing, that of visible reality and an hermetic enclosure, that of mystery- would never be a solipsistic exercise, closed around itself, but fruit of a rich interaction between the thinker and his city. An interaction from which a philosopher’s clear awareness of public vocation is born, and consequently his eagerness to shape his city, to produce beautiful work in it which invites observers to think and reflect. Barcelona is so present in his work, that in his book City over City (2001) it can be guessed between the lines. There he conceives his philosophy like an ideal city, formed by four neighbourhoods: philosophical, ethical, artistic and religious. An ideal city that interacts with the real city.

“A visible city supported by submerged, buried, labyrinthine cities, representing the different strata of cities superimposed by history”

Trías follows Wittgenstein’s reflections on the conception of human language, understood as a city that amalgamates an old town, reorganized by modern forms of rationalization; or, like Freud, who thought of Rome as a “city over a city”, a visible city supported by submerged, buried, labyrinthine cities, representing the different strata of cities superimposed by history. Trías understands his ideal city as a symbolic model of his beloved Barcelona, inspired in turn by Joseph Rykwert’s analysis of the founding rites of cities in the ancient world.

FROM THE OLD TOWN TO THE EIXAMPLE, THE CLARIFYING MODERNITY

Following that beautiful metaphor, Trías conceives the medieval city -that of the cathedral and the Jewish quarter, of the guilds and craftsmen- as the old town, which hides a religious symbolism. That of cathedral Europe, with its love for stone, verticality and light; with its organic-spiritual conception in the form of an ascending tree, and its spectacular Gothic arches. Without forgetting the powerful Catalan Romanesque, treasured in the MNAC today, with its Pantocrators and mural paintings impregnated with colours that will determine the vision and the imagination of strollers through Barcelona. Trías’ strolling through the medieval city also reveals the Arab and Jewish trace in Barcelona, which speaks of a strange interreligious dialogue: the three great monotheisms of the past were hybridised in fascinating ways, such as the oriental tradition of courtly love, which has shaped the passionate erotic of the Mediterranean man in this part of the world.

This old city centre has been expanded, clarified and complemented by the famous Cerdà plan, with its Ensanche right and left that unite the different original town halls (Gracia, Sarrià, etc.) as a dense mesh, scattered in the true “city of cities” that is Barcelona. Here functionalism, aesthetics, beauty and practicality go hand in hand, configuring a distinctive, characteristic and unmistakable identity. In the same way, Trías always understood Modernity not as an attempt to suppress the symbolic-religious world of the medieval, but as the act of becoming aware, clarifying and elevating the mysterious character of sacred things to transparency. This Modernity that knows how to dialogue with the past, which is projected utopically but with a foundation, is at the heart of Trías’ work, as a result of his relationship with Barcelona.

“Trías always understood Modernity not as an attempt to suppress the symbolic-religious world of the medieval, but as the act of becoming aware, clarifying and elevating the mysterious character of sacred things to transparency”

The “ethical neighbourhood” of which Trías speaks corresponds to the border subject who, in the elevation, rises to hear the imperative voice that commands it to be what it already is: a border subject, one capable of tapping into the village’s endogamous instances and the centrifugal requirements of the global casino, through the awareness of belonging to a civic centre, at the origin of the city.

THE ARCHITECTURAL REVOLUTION AND THE CIVIC SPIRIT

That is why Trías always maintained the dream of that Barcelona, heiress of the different Olympic venues, that knew how to correctly mix tradition and modernity, maintaining the balance between the spirit of the earth and a modernity with a human face. The imprint of the architecture made in the 70s, 80s and 90s in Barcelona -a time when he was a professor at the School of Architecture of Barcelona- shows his interest in the different revolutions in the forms of space and time that the School of Barcelona’s new urbanism introduced. His fine perception for everything that happened in the city in recent decades shows the avant-garde of his philosophical proposal, the clarity of his view on the new conditions of a city in perpetual change, in continuous renewal.

This love for Barcelona is evident in the civic sense that Trías believed to be characteristic of Barcelona, as he shows in his revision of Joan Maragall’s ideas. Trías had the character of a wise man, bourgeois and civic, capable of uniting tradition and modernity and opening himself -with innate interest and curiosity- to new things, without losing the most genuine of his own traditions.

“His love for Barcelona is evident in the civic sense that Trías believed to be characteristic of Barcelona”

For him, a sense of congenital hospitality and a civic love were the best Catalan traits and could be summarised in Barcelona’s citizens. He believed in Maragall’s “Ode to Barcelona”, which called for coexistence among all the classes and strata that make up the city and established the ethical-linguistic capacity to ask for and give forgiveness, as the identifying attribute of those who have a conscience. In civic terms, the dream of a global vision, of a Promethean and inhuman nature -perhaps the dream that took hold in the 20s and 30s of certain megalomaniac projects during the expansion of New York- was to give way to a human and cordial labyrinthine city like Barcelona.

THE MARITIME BARCELONA, A BORDER CITY

Perhaps because he was born at a time when Barcelona lived with “its back to the sea”, there is no reference to Barcelona’s maritime character in his work. However, I think that his formulation of the border character of the human condition is best reflected in Barcelona, a Mediterranean city. Trías always loved the sea, marine life, as he was also an exquisite gourmet (seafood, paellas, fish stews), and a regular visitor of the Barceloneta.

His greatest pleasure was walking down to the sea, where the Universitat Pompeu Fabra is located. Then walking down the new seafront promenades, built for the Olympic games of 1992, and having lunch in front of the sea. The sea is the perfect symbol of the limit that unites and separates two shores: that of the known and that of the unknown. A Barcelona projected towards the sea in a conflictive relationship with it is the living and real figure of its border condition, the central core of the thought of one of the great philosophers of the 20th century, who was undoubtedly an eminent man from Barcelona.